In early 1995, Nick Saban

and I were walking across the Michigan State campus in East Lansing. He waved his hand in a sweeping motion and brought up

his initial impressions of the place when he joined head coach George Perles’ staff as a young Spartans assistant in

1983.

“I thought, ‘Now this is what a college campus should be like,’” Saban told me.

“The trees. The river. It’s like a national park with a college in it.”

This conversation

was before Nick Saban was Nick Saban. He had just returned to Michigan State

and taken over as the Spartans’ head coach after serving four seasons as Bill Belichick’s defensive coordinator

with the Cleveland Browns. And it was early in my year-long, occasional visiting with and observing Saban when I was at The Sporting News, using Michigan State as

the example of what a major program goes through in the first year after a coaching change. I never was embedded. I checked

in and out of East Lansing, wedging the visits among my other story assignments.

Editor John Rawlings was terrific

about assigning his writers to stories he and his staff picked out, but then during our quarterly meetings in St. Louis allowing

each of us to claim other pieces we really wanted to do, as long as we could

sell him on them. I had the coaching transition story in mind for a long time, and we agreed I would tackle the concept as

a year-long project. When we decided on Michigan State as the subject following the announcement of Perles’ firing late

in the 1994 season, we didn’t know who his successor would be.

The choice of the program to follow

was fortuitous. Saban heeded the recommendation of Browns VP Kevin Byrne, who knew me and told him that going along with the

story — within realistic parameters — would be good for the MSU program.

Now, years later, Saban

is the renowned Alabama coach who came up just short of winning his eighth national title on Monday night in a 33-18 loss

to Georgia in the College Football Playoff championship game. His national titles came at Louisiana State in 2003, then with

the Crimson Tide in 2009, ’11, ’12, ’15, ’17 and '20.

Even while working

at a school where Paul “Bear” Bryant won six national titles, Saban now is the consensus choice as, in the parlance

of the day, college coaching’s GOAT — Greatest of All Time.

That was all to come.

When I popped in

and out of East Lansing that year, Saban was only in his second season as a collegiate head coach, following a one-season

stint at Toledo.

The MSU job came open because while Perles did a good job early in his 12-season tenure, the program

deteriorated, both on and off the field. After his firing, Perles and the MSU administration agreed he would coach the Spartans

the rest of the season, through the final game at Penn State.

Saban was “mentioned”

as a candidate from the start. He was Perles’ defensive coordinator for MSU’s 1987 Big Ten and Rose Bowl championship

team, was the Houston Oilers’ defensive backs coach for the next two seasons, and then spent the one year as head coach

at Toledo, going 9–2 in 1990 before moving on to the Browns.

Five days before the MSU–Penn State game,

Saban met the MSU selection committee at a Detroit hotel. The committee had six other members, but MSU President Peter McPherson

was in charge. Saban had two perceptions working against him: 1, He might

be an NFL coach at heart because he had left both Michigan State and Toledo to go to the pro game; and, 2, He was tied to

Perles and wouldn’t represent a completely fresh start. For reasons that would come into focus later, McPherson felt

that was needed.

Saban told the committee he didn’t want just any head-coaching job; he wanted this one.

The

coach and his wife met at a junior high science camp, and their relationship overcame a rough start when Nick stood up Terry

on their first date — bird watching at 5 a.m. They were married for more than a decade before Nick Jr. and Kristen arrived,

and by the mid-1990s, Terry and Nick were concerned about where their children would be raised. A college town would be nice;

the Lansing area would be ideal.

The Perles issue? Saban argued he was his own man and not Perles’ or anyone

else’s. In fact, as a young defensive backs coach, Saban had recovered from being part of volatile coach Earle Bruce’s

mass firing of his Ohio State defensive staff after a 9-3 season in 1980. (Later, Bruce finished out his coaching career at

Colorado State.) It was safe to assume, too, that Saban implied that he had differences of philosophy with Perles that contributed

to his decision to leave East Lansing for the Oilers and the NFL as a position coach.

Another problem was that

McPherson was impressed with Fran Ganter, Penn State’s offensive coordinator.

I went to University Park

and saw Penn State steamroll MSU 59–31 in Perles’ final game. Afterward, I was among those listening, dumbfounded,

as Perles conducted a rambling filibuster before anyone could even ask a question. His bottom-line point was that the pressure

to win, and perhaps cut corners to do it, was greater than ever.

“I worry about the young coaches because

there’s so much pressure on them to win because the dollar is so tight nowadays with gender equity,” he said.

Saban

was the runner-up in the search, but as often happens — whether it comes out publicly or not — the runner-up got

the job. Five days after the final game, Gantner told McPherson thanks, but no thanks; he was staying at Penn State. That

was a Friday night, and shortly before midnight, McPherson called Saban and offered him the job.

The second choice

said yes.

His five-year contract called for a starting base salary of $135,000,

plus a $150,000 bonus in the year 2000 if:

- The team’s grade-point average

improved from 2.3 during Perles’ last year, to at least 2.55 during the 1999–2000 academic year.

- The Spartans stayed clean in the eyes of the NCAA.

- Saban’s teams won two-thirds of their games.

Of course, if he accomplished

the first two points but not the third, chances were Saban would be fired before 2000. He knew the rules of the game. We all

did.

The week after the announcement, the Browns beat the Dallas Cowboys in Texas Stadium. Saban traveled

that night to East Lansing and met with the MSU players. The room was silent. Players were afraid to exhale too loudly lest

they get marked as troublemakers. They later said Saban didn’t smile once.

“This is the way we’re

going to do things around here — my way,” Saban declared. He then told them that he still was coaching two starting

Browns linebackers who played at MSU, and he held them up as examples.

“I love Michigan State,”

Saban said, “Carl Banks loves Michigan State, Bill Johnson loves Michigan State, and I sit in a room with them every

day. If one of you guys does something to embarrass yourself and this program, it hurts every one of us. But you hurt yourself

worse, and you’re responsible for your actions.”

He brought up the classroom, asking, “So

what happens if you aren’t interested in getting a legitimate education?” Then he answered it. “We probably

will have some problems down the road.”

Like all new head coaches, Saban sifted through the mixed messages about

what we want out of college football. He did it in the style of a man who neatly orders his life as if it were divided into

periods, announced by an equipment manager with a blowhorn.

Or by a coal mine’s end-of-the-shift whistle.

In 1968, Saban’s senior year at Monongah High School in West Virginia, seventy-eight

men died in an accident at the nearby mine. Saban had run across some of the coal miners during his hitchhiking travels around

the sparsely populated region where an upturned thumb turned any spot into a bus stop. Saban, the son of a service station

owner, was Monongah High’s quarterback.

At Kent State, he was a defensive back and shortstop, and a horrified

freshman on May 4, 1970, when members of the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four students.

Reflecting the calendar’s

relentlessness, the generation of men of the 1960s and 1970s who questioned authority later became authority, telling college

students: You will do this. When they happened to be major college football coaches who had just gotten their reputation-defining

opportunities, they faced the challenges about honor. Specifically, when taking over a program in a down cycle, can you afford

to have honor?

I wasn’t so sure. I looked around a college football landscape in which it seemed as if known renegades

were getting ahead and even landing NFL coaching jobs. The truth was — and still is — that if a coach wins by

cutting corners, he still will be stamped a “winner.” I’ve always wondered whether we are telling coaches

that honor didn’t really matter.

Saban was insistent that it did.

“It’s almost

like I have a lot of money but I stole it all, so do I feel good about being rich?” Saban told me at the Browns’

offices in Berea, Ohio, after he had accepted the MSU job but still was working as Belichick’s defensive coordinator.

“Or is it better if I worked hard, earned every cent, and developed financial security for myself because of my work

ethic and willingness to do things correctly? I’d rather do it the second way.”

When I met with

Saban the first time, Cleveland had two games remaining, the first a Central Division showdown at Pittsburgh. On Wednesday

morning of that week, Saban drove to the Browns’ headquarters in the dark. He dialed area code 517 on his car phone.

The ringing awakened Gary Van Dam, one of the holdovers from the Perles staff. Before he could wipe the sleep from his eyes,

Van Dam heard his new boss rattle off what he wanted done in East Lansing that day.

It was 6:15.

“I’m

basically the head coach at Michigan State when I’m in my car,” Saban said.

Saban

coordinated the academic program during his stint under Perles, and he was unapologetic about his belief in giving academically

questionable players chances to prove themselves in school — but also not letting them skate through. His first financial

request of the Downtown Coaches Club, MSU’s football booster club, was for the club to buy five desktop computers for

the players. That request was ahead of the curve; in the upcoming years, computer labs would become important elements in

recruiting.

“I’ve recruited too many guys who have been willing to make the commitment to improve the

quality of their life,” Saban told me, “and they got the education. Right now we’re saying in the NCAA that

those guys shouldn’t get the opportunity, and I don’t necessarily agree with that.”

In early January

1995, the Steelers ran over Saban’s Cleveland defense in a Saturday playoff blowout. Saban was in East Lansing that

night, eating with 15 high school prospects. On Monday, he returned to Cleveland, cleaned out his locker at the Browns’

offices, and spoke frankly with Belichick about the defense. He was in East Lansing the next day. He finally was Michigan

State’s head coach, full time.

For the next few weeks, or until the Feb. 1 letter of intent signing

date, Saban felt like a “hot potato” tossed around by his staff. One day, he visited six prospects in their homes

— five in Detroit and one in Toledo.

The new staff’s first 20-player freshman recruiting class included

nine linemen, where the Spartans needed the most help.

During the next few months, Saban learned that an alarming

number of Spartans were having academic problems. He also discovered that the conditioning program had slipped in the seven

years since he left Perles’s staff.

“George gave me a great opportunity professionally in 1983,”

Saban told me. “We took over a 2–9 situation and in five years built it to a top-10 team, a Big Ten championship,

and a Rose Bowl victory. I think George did an outstanding job. What has happened since that time, I really don’t know.

I wasn’t here, but we certainly don’t have the quality of players.”

Saban met with every holdover

scholarship player. As the new staff established its authority, there were some grumbles, but the players seemed to gradually

come around.

“He kind of shocked us because the strength and conditioning programs were so intense,” Tony

Banks, the holdover quarterback, said. “A lot of us weren’t in very good shape. We were a lot bigger. Guys were

rebelling, talking about transferring, about not playing. But then we started seeing a difference in the way we looked. A

lot of the linemen dropped a lot of weight.”

The Sabans commissioned a builder to construct their dream

home.

While waiting, they lived in the home offered to them by MSU faculty member Jim Cash — a screenwriter

who co-wrote “Top Gun.” Cash’s mother-in-law usually lived in the home, but she visited Florida in

the winter.

Mindful of the post–NFL season family routine, young Kristen Saban kept asking, “Daddy, when

are we going to see Mickey and Minnie?” Nick had to say there would be no Disney vacation for the Sabans that spring.

In

late February, Saban strayed from his normally cautious character by announcing on the public-address system at a Michigan

State–Michigan basketball game that the Spartans need the help of the home crowd in the second half “to kick Michigan’s

—.” It both drew a lot of attention and sent a message. He would pick his spots, but he would ignore protocol

when it served his purpose.

I returned to East Lansing during the Spartans’ spring practices. One of the

most interesting aspects was to walk through packs of fans and eavesdrop. Generally, it seemed to be: This guy means

business! I also was struck by the fact that he had been Perles’s defensive coordinator only a few years earlier,

but it had been at a time when assistant coaches — even coordinators — could stay somewhat under the radar.

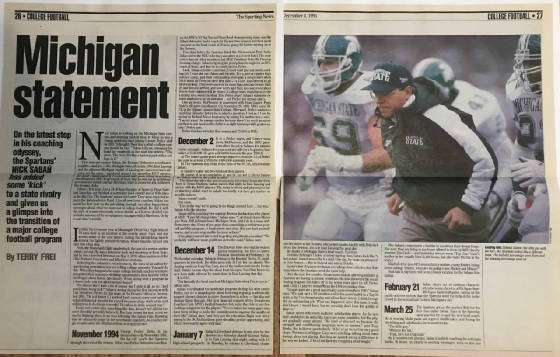

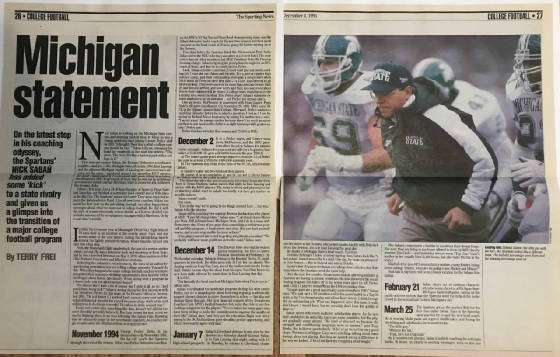

At

the first Saturday open practice, Saban wore khaki pants and a green windbreaker, and during the stretching and calisthenics,

he seemed nondescript — so nondescript that I heard some fans trying to make sure they were looking at the right coach.

“The

little guy.”

“Without the hat.”

“Yeah, he’s not a big man.”

Fifteen

minutes into practice, Saban was actively coaching the defensive backs, but he also made points to the whole team. He caught

fullback Robert Dozier trash-talking and hollered at him: “I don’t want to have that out here, understand?”

Then he turned to the entire team. “Understand?” he yelled.

At the end of the practice, Saban made

a surprisingly soft-spoken speech to the players about how much more they have to accomplish during the remainder of spring

practice. Dozier approached Saban, then walked toward the locker room with his new coach. Dozier tried to explain the trash-talking

incident. Saban quietly listened, and said something along the lines of: It’s

all right, no big deal, don’t worry. Just don’t let it happen again.

I left East Lansing

thinking that the cupboard was bare, that recruiting had slipped significantly in Perles’s final seasons, and that Saban

was going to take his lumps in his first season. I guessed the Spartans would win three or four games, max, but the important

thing would be creating the impression that Saban was the right man in the right place to ultimately get the program turned

around.

As spring practice wound down, Jim Cash’s mother-in-law returned from Florida, and the Sabans moved

into an apartment near campus. But Saban still wasn’t around much. He was involved in early spring recruiting and met

— or reacquainted himself — with Midwest high school coaches.

May 4, shortly after

spring practice ended, was the 25th anniversary of the Kent State massacre.

The school’s ROTC building

had been burned down on that Saturday night in 1970, and Governor James Rhodes dispatched the Ohio National Guard to Kent.

“Martial law was declared,” Saban told me. “It was a war zone. I mean, the place looked like Saigon, with

all the damage that had been done and the choppers circling overhead.”

Demonstrators planned a protest

of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia for that Monday. Saban had an 11 a.m. class in the education building. His friend and teammate,

Phil Witherspoon, wanted to watch the protest on Blanket Hill; Saban lobbied for lunch. They went to the cafeteria. At 12:24

p.m., 13 young people were shot. At about 12:30, as Saban and Witherspoon approached Blanket Hill, they heard sirens.

“It

was shocking to see the people hurt and the large pools of blood,” Saban said.

Four of the wounded died;

one, Allison Krause, was in Saban’s English class.

On June 1, linebacker Ike Reese, the Spartans’ leading

tackler as a freshman in 1994, was involved in a fight outside an East Lansing club. He eventually pleaded no contest to disorderly

conduct in August and spent two days in jail. Saban allowed him to remain in the program.

“People make

mistakes in this world,” Saban said. “The question is, do I think he’d do it again? But you can’t

change your value judgment based on how good any player is.”

Over the summer, Dozier (the former trash-talker)

and guard Jason Strayhom — both backups — were charged with conspiracy to distribute marijuana. After reading

the police reports and talking to the players and their parents, Saban indefinitely suspended both players. Neither was on

the roster for the 1995 season.

“The most frustrating thing for me as a college coach is if a guy does something

wrong socially, however minimal it is, it’s almost like it’s your responsibility, because he’s a part of

your team,” Saban told me. “I don’t think you can control anyone’s behavior to that degree. I mean,

I don’t know what my four-year-old is going to do when she goes down the street on her bicycle, and she’s done

a few embarrassing things. I don’t think you should tolerate those things either, but at the same time you have to have

compassion for the people involved.”

In the summer, the Sabans moved into their quickly constructed new home

and made their annual trip with friends to Myrtle Beach, S.C. Saban also appeared in Chicago for three days at the Big Ten

Conference kickoff. “No offense,” he said, ruffling some feathers, but the day of golf and two days of media sessions

were keeping him away from football preparation, and he looked very much like an impatient man.

By then, Saban was

working under a new athletic director. Merrily Dean Baker was out, replaced by Merritt Norvell Jr., who played for Wisconsin’s

1963 Rose Bowl team. (Aside: In late 2021, Merritt Norvell's son, Jay, was named the new head coach at Colorado

State.) Merritt Norvell told reporters that he was “comfortable” with Saban. But the mandate was familiar.

“It’s

important to win,” Norvell said. “It’s also important to make sure your kids graduate, important you get

leadership within the department from the coaches, and important that people conduct themselves properly. But if winning wasn’t

important, we wouldn’t have a stadium that seats 72,000 people.”

The Spartans

got off to a 2–2–1 start under Saban, recovering from a 50–10 season-opening loss to Nebraska. Game

six was on the road at Illinois. On the plane ride to Champaign, Saban played checkers with little Nick. Little

Nick won. Big Nick insisted he didn’t throw the match. And he wondered, could this be an omen?

In Champaign, Saban made his weekly pregame speech to the

team.

“When I was a kid in West Virginia, I went fishin’ a lot,” Saban said.

“One

time, there was this old man fishin’ nearby. He was catching them right and left. Big ones, little ones. But I noticed

he was throwing all the big ones back and keeping only the little ones. Drove me nuts. So finally I went over and asked him,

‘Why do you throw back all the big ones?’ He looked at me and says, ‘I only have a ten-inch frying pan.’”

The

players laughed.

Saban waited.

“That’s the way you guys think sometimes,” he said.

He

challenged them to set their sights higher.

The players made that story their tongue-in-cheek rallying cry the next

afternoon: “Win one for the small frying pan.” And they knocked off the Illini 27–21.

Big Nick won the

checkers match on the way home.

The next week, the Spartans faced Minnesota at home. During

the week, Saban said he was enjoying his return to college football — and MSU — almost as much as anticipated.

“Here,

you try and instill a positive attitude, get them some goals and objectives,” he told me. “Most pro guys, regardless

of what the motivation is, you don’t have to instill that. They might want to do it for the wrong reason, but they still

want to do it. If they don’t? You find another player. Here, you have to develop the player you have, all the way around

— physically, mentally, emotionally. But I think that’s the fun of college coaching.”

Perles, still living

in the Lansing area, called his own news conference and announced he had dropped his lawsuit against MSU, one he filed because

the university was dragging its feet on finalizing a settlement on his contract.

The speculation was that MSU

was stalling because after Saban took the job, the news broke that the university and the NCAA were investigating the football

program for possible violations during the Perles tenure. (As it turned out, the investigation actually began a month before

Perles’ firing.) If the NCAA imposed sanctions, then MSU could try to say that Perles — who was being paid in

the interim — wasn’t owed another dime.

Could the NCAA investigation hurt the Saban program? “I

think it could,” Saban told me. “I don’t know how to say this without . . .”

He paused.

“I

don’t really know of anything [against NCAA rules] of a significant nature that had happened here. Of course, I wasn’t

here for part of the time, and I know there’s nothing that has happened since I have been here. . . . The only thing

I feel bad about is if there’s some punishment for the university and the program now, it’s not really justified

for the people who are here now who would be punished.”

On Friday, Saban slipped into his seat next to

the podium at the Downtown Coaches Club meeting at 12:15 p.m., moments before the program began. Downtown Coaches President

Gary Thomas, a retired fireman and a Saban fan, told me that Saban was “so businesslike. From week to week, I don’t

even know if he’s going to make it here. He’s got the most disciplined schedule I’ve ever seen. Some guys

are hour to hour; he’s minute to minute.”

The room at an East Lansing restaurant was packed: 239 paying

customers at $11 a head for lunch and a raffle ticket. (I didn’t win.) When Ike Reese, the linebacker, nervously accepted

his defensive player of the week plaque and mentioned that the Spartans had “another good game plan” for Minnesota,

Saban leaned over, smiled, and said something to Reese.

In his turn at the microphone, Saban said, “It’s

very encouraging to me that Ike has approved the game plan for the week.” The audience laughed. “Better get laughs

now,” Saban said, looking at Reese, “because when we watch the film on Monday, I’ll either approve or disapprove

of the execution of that game plan.”

On Saturday, the Spartans trailed Minnesota, 31–21, after three

quarters, but rallied for the 34–31 victory. Banks returned to the lineup after missing time with an ankle injury, throwing

for 309 yards and two touchdowns.

Saban had to caution his players not to look ahead to bowl possibilities. “I

guess the attitude of the players has progressed to the point where we really believe we can win,” Saban said. “I

don’t think we had that kind of character as a team earlier in the year.”

They came back to earth

on week eight, falling 45–14 to Wisconsin.

That didn’t instill a lot of confidence heading into

the Nov. 4 rivalry game at home with seventh-ranked Michigan. All week long, Saban reminded his players: You know, there aren’t going to be very many days in your life when you don’t run across somebody

from the University of Michigan. Wouldn’t you like to be able to talk about the year you beat their —–? It

was the kicker to his message at the Michigan–MSU basketball game.

Michigan

scored with 3:38 left to take a 25–21 lead.

MSU drove 88 yards, and Banks threw the game-winning, 25

yard touchdown pass to Nigea Carter with 1:24 remaining. The Spartans hung on and the raucous celebration of the 28-25

win lasted into the wee hours in East Lansing.

A 35–14 victory over Indiana in week 10 made the Spartans bowl

eligible, at 6–3–1. Some seemed concerned that Michigan and Penn State might get more coveted bowl slots despite

sub-par seasons because of their programs’ reputations. But the important thing in East Lansing was that the Spartans

were going to go to a bowl, period.

At the regular-season finale against Penn State, one Spartan Stadium

end-zone sign proclaimed to ESPN viewers: Saban is God. A year earlier, when

these teams met, the Michigan State coach already had been told he wasn’t wanted any longer and the top candidate for

his job was coaching the Penn State offense. Now, much to my own surprise, given my preseason expectations for the Spartans,

the second choice for the MSU job was within reach of a seven-victory season, a third-place Big Ten finish, and a mid-rung

bowl berth.

Trailing 20–17, Penn State started on its 27 with 1:45 to play. Finally, on a third-and-goal from

the 4, quarterback Wally Richardson dumped an inside screen to Bobby Engram, who stretched the ball across the goal line with

eight seconds remaining and Penn State had pulled out a 24-20 win.

The Spartans finished 4-3-1 in the Big Ten.

Still,

Saban said that he was proud of a team that was favored just twice all season and came so far since that opening-week embarrassment

against Nebraska. The Spartans lost to Louisiana State in the Independence Bowl and finished 6–5–1. That kind

of season most likely wouldn’t be good enough for a fifth-year coach, but it was praiseworthy under the first-year circumstances

at Michigan State. It was the best first season for a Spartan coach since Biggie Munn (7–2) in 1947.

Saban seemed to

have won over the Spartan constituency. Yet what would become a familiar pattern with his players was developing. He was respected,

but he was not warm and fuzzy or beloved.

The NCAA decision came down in September 1996, early in Saban’s

second season. MSU already had forfeited its five wins in 1994, Perles’ final season, as part of self-reporting and

penalizing. The NCAA cited a “lack of institutional control” and mostly went along with the university’s

self-imposed penalties. The end result was the loss of seven scholarships for the 1997-98 school year and a cut by one in

the number of coaches who could recruit off-campus during the upcoming recruiting period. The program also was placed on probation

for four years, retroactive to December 1, 1995, but the worst fears — bans on bowl-game or television appearances —

weren’t realized.

Saban made it through that.

He ended up staying only five seasons,

though.

After the Spartans went 9–2 in the 1999 regular season, giving MSU a 34–24–1 record

under him, he accepted the Louisiana State job and didn’t even coach the Spartans in the Citrus Bowl against Florida.

He went through some angst because he and his family had made friends in the Lansing area and he regretted leaving them behind,

but he moved on.

His reasons? A huge contract and his disillusionment with

what he viewed as MSU’s half-hearted commitment to the football program. He won that 2003 national championship at LSU,

spent two seasons as the coach of the Dolphins, and then bailed out again to go to Alabama. He took considerable criticism

for denying interest in the Alabama job during the Dolphins’ season. Despite his image as a “college coach,”

the Miami stint with his third in the NFL.

As we’ve seen after the national championships at LSU and Alabama,

the guy can coach — albeit with better facilities, resources, and support than he had at Michigan State. But

that first year in East Lansing was full of foreshadowing.

The story ran in December 1995, and while I was proud of

it, my major regret was not saving all the notes, tapes and even the original epic-length first draft to explore the possibility

of turning the magazine piece into a book. Among the notable cuts were the tale of how he put a staff together. The point,

though, was that the story from the start was intended to be about a year of transition in a major college football program,

not a narrative of a season.

But I also realized I was pushing the envelope with Saban,

who always was civil in our talks. I liked him. In the years since, I’ve often wished he would display what I found

to be his sharp sense of humor more often in he public eye. Of course, the landscape has changed considerably since 1995,

and a coach letting down his guard at a podium in the often scripted and stilted mass media availabilities of today is neither

common nor wise.

In 1995, I thought he was a terrific coach.

But I admit I didn’t see this coming.

(First two pages...)