|

|

HOMEInstitutional Knowledge commentariesBioFilm rights, Screenplays, RepresentationOlympic Affair: Hitler's Siren and America's HeroTHE WITCH'S SEASONThird Down and a War to GoHORNS, HOGS, AND NIXON COMING'77: DENVER, THE BRONCOS, AND A COMING OF AGEMarch 1939: Before the MadnessPLAYING PIANO IN A BROTHELSave By RoyA Selection of Terry Frei's writing about World War II heroesThe OregonianThe Sporting NewsDenver PostESPN.comGreeley TribunePress CredentialsThey Call Me "Mr. De": The Story of Columbine's Heart, Resilience and RecoveryOlympic Affair: Chapter 1, Leni's VisitOlympic Affair: Chapter 15, Aren't You Thomas Wolfe?The Witch's Season Excerpt: Air Force Game, Bitter Protest, a Single ShotThird Down and a War to Go genesis: Grateful for the Guard, Jerry FreiHoneymooners Meet the Boys of SummerTommy Lasorda, the Spokane Indians, and My Summer of '70Smoke 'em inside: On Ball Four and Jim BoutonEarthquake at the World SeriesMosquito BowlA Year with Nick Saban before he was NICK SABANJon Hassler, Terry Kay and other favorite novelistsKids' sports books: The ClassicsBig Bill Ficke's Big HeartBob Bell's Food For Thought

|

(National Archives. NA-242-HD-245-1.) 1 Leni’s Visit

Simla, Colorado: Tuesday, September 3, 1974

The cook squinted at the ticket on the wheel facing him, pretending to be deciphering the handwritten lunch order.

“What language is that?” he asked softly.

“English,” said the perky teenaged waitress, pointing at the ticket with her pen. “Can’t you read?”

“No, I mean—”

“I know what you meant,” she said impishly, nodding almost imperceptibly over her shoulder, in the direction of the man and woman conversing in a window booth. “German, I think. Or maybe Spanish.”

Though her platinum hair unmistakably was dyed, the woman looked to be in her early sixties. Her smart pantsuit and haughtiness made her seem unwilling to concede anything beyond mid-fifties, even to herself. On the other side of the table, the skinny young man with shaggy blond hair was deferential, sipping his coffee as the woman animatedly made a point with both hands and a Teutonic torrent. Werner Vass had just turned thirty and he was accustomed to listening.

The only customer at the four-seat counter, a middle-aged regular who owned the Simla Grocery next door, devoured the final bite of a hamburger and wiped his mouth with the paper napkin.

“Kristy,” he called out to the waitress. “Half cup for the road, will ya?” As she poured the coffee, he told her bitterly, “It’s German, all right. I hope I made her a goddamn widow.” Kristy sneaked a look at the booth, where the woman continued her monologue, oblivious.

The grocer raised his cup, took several swallows, and then slammed it down. He dropped four one-dollar bills on the counter and marched out.

As the cook finished assembling the Germans’ sandwiches and slapped them on the plates—there were no “presentation” issues at the Simla Café— a stocky man in a dark suit, with a chauffeur’s hat tucked under one arm, entered and approached the booth. The Germans made no move to make room for him.

“All gassed up,” he said.

The woman responded in clipped and accented English. “How long will it take us to travel to the Denver airport?”

“About two hours, ma’am.”

Werner Vass looked at his watch and rattled off something in German to the woman. She nodded emphatically. Turning to the chauffeur, Vass said, “After we finish here, we would like to tour the area a bit more before leaving for Denver.”

“Yes, sir. I’ll be outside.”

Kristy delivered the food, sliding the plates in front of them. Then she stepped back, put her hands together and smiled. “Is there anything else I can get you?”

The woman’s return smile wasn’t warm; it was a formality. It was a smile offered in accompaniment with a request. “Perhaps some information,” she said. “How long you have lived in Simla?”

“All my life,” Kristy said. “Except last year at CU . . . at college.” Self-conscious, she added, “I’m taking this semester off. Going back next . . .”

The woman cut her off. “Are you or the cook aware of Glenn Morris?”

“The Olympics guy, right?”

“That’s correct.”

“Well, Eddie just moved here a couple of years ago. So I don’t think he does. But there’s a display case about him at the school and they always cover him in Modern American History. Won a gold medal in something at the Olympics in the twenties somewhere in . . .”

Kristy’s pause was momentary, but something was clicking.

“ . . . in Germany.”

“Berlin,” the woman said, scolding. “The decathlon. And 1936.”

“I guess that’s why I only got a ‘C,’” Kristy said lightly.

The woman didn’t smile.

Kristy squinted. “Didn’t he just die, too?”

“In January,” the woman said flatly. “In California.”

“Did you know him?”

“Ye-e-e-e-s.” The woman drew out the word, as if she was deciding whether it would be the final one or she’d keep going. She didn’t keep going. Kristy interpreted the awkward pause as an excuse to leave and let them eat.

When Kristy dropped off the check, Vass perused it and said, without looking up, “You say there is a display honoring Glenn Morris at the town school?”

“Outside the gym.”

“Where is this school?”

The waitress pointed north. “A block up Caribou, right on Pueblo, up the hill and you can’t miss it. Gym’s the first thing you come to. School just started today.”

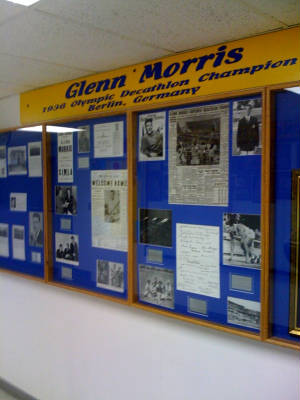

A few minutes later, Vass stood back as the German woman, transfixed, looked over the glassed-in display. A bell rang and students scurried past. A sign in school colors, blue lettering on yellow background, stretched above the cases.

GLENN MORRIS 1936 Olympic Decathlon Champion Berlin, Germany

Pictures from his youth established that Glenn had been a student leader and star athlete, both at Simla High and Colorado Agricultural College in Fort Collins, and handsome even then. Front pages from Colorado newspapers told of Morris’s Olympic triumph (“GLENN MORRIS CAPTURES DECATHLON CROWN”) and his tumultuous welcome home to Colorado. The woman lingered at each.

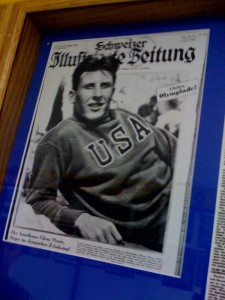

A front cover of a German tabloid showed Morris, dark-haired and lean, yet chiseled, wearing a USA sweatshirt, smiling slyly at the camera, resting on one elbow as he lounged on grass. He was featured so prominently, his head even covered up part of the newspaper name. The editors apparently believed their readership didn’t need to be reminded of the title, but wanted to see the American star.

Finally, she came to a newspaper picture of Morris in a dark USA pullover sweater, and a white collared shirt underneath, sitting on the edge of a bed and writing a note on the adjacent tiny desk. A framed picture of a prim young woman, her hair tied back, was next to his writing pad. The picture’s headline and caption proclaimed:

REMEMBERS GIRL HE LEFT BEHIND Glenn Morris, the Colorado boy who is America’s hope in the decathlon, takes time out to write his girl back home.

The German woman lingered.

Vass solicitously placed a hand on her shoulder. “Er sollte bei mir übernachtet,” she snapped.

She pulled away from his hand and moved toward the school doors. They hadn’t noticed that three boys had stopped behind them. It was as if a pedestrian looked up at the sky. These kids wanted to take a closer look at what was drawing the strangers’ interest.

Starting in pursuit of the woman, Vass bumped one boy. “I’m sorry,” the German said. “Excuse me.” The kid pointed to the woman storming off. “What

did she say?”

Vass slowed and turned. Backing up, he told them, “She said . . . ‘He should have stayed with me.’”

* * *

With no orders pending and only three customers in the cafe, the cook poured himself coffee, gathered up a couple of sections from the Denver Post piled by the cash register, sat at the counter, lit a cigarette, and started reading. In the front section, he skimmed pieces summing up the early days of the Gerald Ford administration and Richard Nixon’s hermit-like existence since his resignation. In sports, he checked on the status of Denver Broncos quarterback Charley Johnson’s wobbly knees. On the cover of the Rocky Mountain West section, he read of the freshman cadets reporting to the Air Force Academy fifty miles away in Colorado Springs and laughed at the pictures of hair shorn as barbers showed no mercy. He opened the section, flipped a couple of pages and came to the beginning of the “Entertainment and Arts” pages.

The lead story startled him. Above the headline were three face shots of the woman who a few minutes earlier had been sitting in the booth behind him. All three were from the same interview session. In the first, she smiled. In the middle, she was pensive. In the third, she decisively was making a point with her hand.

The cook read the story twice.

“Nazi” Controversy Mars Telluride Film Festival

By Steven Garrison Western Slope Bureau

TELLURIDE—By most standards, the inaugural Telluride Film Festival at the historic Sheridan Opera House in this southwestern Colorado mountain town was a spectacular success over the weekend, drawing marquee names, producing overflow crowds, and establishing itself as a can’t-miss stop on the festival circuit.

Talks from acclaimed “Godfather” director Francis Ford Coppola and iconic actress Gloria Swanson were popular, but the appearance of German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, noted and criticized for her connection to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Third Reich, drew the most attention.

Showings of two of the famed director’s works—“Blue Light,” a 1932 drama Riefenstahl also starred in, and Part 2 of “Olympia,” a documentary about the 1936 Olympics in Berlin—were respectfully, even reverentially, received in the showcase evening’s session. Many “Olympia” viewers were surprised to note that Riefenstahl placed a spotlight on a photogenic Coloradoan, American decathlon gold medalist Glenn Morris.

Riefenstahl was given thunderous standing ovations after both films, and also when she was awarded a silver medallion as one of the festival’s main honorees. Her reaction was akin to those of prima ballerinas or opera sopranos, with her blowing kisses, repeatedly mouthing “thank you,” and accepting flowers.

A showing of her most famous film, “Triumph of the Will,” the documentary about the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg, was slotted for 1 a.m., drew a smaller crowd and surprisingly little reaction—positive or negative. During the weekend, security was tight. However, protesters numbered less than a dozen and their actions didn’t disrupt festival events.

Festival organizers, as they had earlier, noted that Riefenstahl never had been a member of the Nazi party.

Riefenstahl, still a striking woman at age 72, consented to interviews with individual reporters in her suite at the Manitou Lodge before the festival began, reiterating her claims that her films were the work of an artist and that she was neither philosophically nor politically aligned with Hitler and the Nazis.

“I am independent, always,” she said. “Hitler said about me that ‘Leni is as stubborn as a donkey.’”

She denied she ever had been romantically involved with the Nazi leader.

“Because I am a woman and because he admired my work, people who were jealous or were looking for a good romantic story say I was his lover,” she stated. “I was never Hitler’s lover. We talked a few times on artistic things. Never politics. He didn’t talk politics with artists.”

Pointing out she was a successful actress and director before turning to documentaries, she asserted she made “Triumph of the Will” only after much convincing from Hitler, who told her that if his propaganda ministry oversaw the project “it would bore everybody.” She said she told Hitler she was ignorant of the inner workings and militia designations of the Nazi Party, but that Hitler saw that as a positive, not a negative. She scoffed at the notion the film was propaganda.

“It is a documentation, a newsreel done artistically,” she claimed.

Swanson, the star of film’s silent age, especially seemed incredulous that some considered Riefenstahl’s presence deserving of criticism. “Why?” she asked. “Is she waving a Nazi flag? I thought Hitler was dead!”

The cook called Kristy over, gestured at the stool next to him, slid the section over on the counter to be in front of her, and asked, with eyebrows raised: “Recognize anyone?”

“That’s her!”

“Sure is. Read it.”

The cook returned to the kitchen. Soon, Kristy poked her head next to the order wheel.

“Okay, I’ve read it,” she announced. “And it figures.”

The cook asked, “How’s it figure?”

“She left a quarter tip.” The grocer burst in, brandishing the same Post section, opened to the

story.

“See!” he demanded, slapping the page with his free hand. “See!”

“Matter of fact, we did,” the cook said dryly.

“I was guessing she was a Nazi bitch, all right,” the grocer said. “Like all those others. We buried our buddies, we liberated the camps, we saw the human skeletons, then we heard about the Kraut bitches saying they had no goddamn idea what Hitler had in mind so give ’em and their kids food and feel sorry for ’em! But man . . .”

Pausing, he shook his head. Then he continued,

“This is The Nazi bitch. What did we do

to deserve this honor?”

The cook shrugged. “Wish we could ask Glenn Morris,” he said. |

||||||||||