Terry Frei

NOTE: Thanks to Brad Hoopes

of rememberandhonor.com, champion of veterans' causes in Northern Colorado, for facilitating the presentation of the French Legion of Honor medal

to the Colorado-connected veterans and for calling my attention to them and their war-time experiences. This is a single-story

compiliation of the multiple individual pieces I did before and after the presentation in Windsor. They're presented in this

order if you want to scroll to read about a specific recipient:

1, Leila Morrison

2, Bill Powell.

3, Philip Daily.

4, Harry Maroncelli.

5, Joe Graham.

Gratitude: French government

honors 6 Coloradan

WWII vets

with

Legion of Honor medal

In February 2019

in Windsor, between Fort Collins and Greeley in Northern Colorado, French Consul General Christophe Lemoine spoke five times

in French, pinned a Legion of Honor medal on an elderly Colorado veteran of the European Theater in World War II, and embraced

the recipient.

Lemoine presented the medal to:

--

Army combat nurse Leila Morrison of Windsor, who came ashore at Omaha Beach shortly after U.S. troops and followed the lines

across Europe, witnessing the horrors of war and of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

-- B-24 pilot Bill Powell of Fort Collins, whose plane was shot down on his 10th

mission before he was interned in the Stalag Luft I prison camp through the remainder of the war in Europe.

-- B-17

tail gunner Philip Daily of Brighton, whose plane went down on his 25th mission before he was taken to Stalag Luft IV, then

survived a forced 86-day, 600-mile march under terrible conditions before the German captors disappeared.

-- B-17 ball turret gunner Harry

Maroncelli of Fort Collins, who made it through a full 35-mission tour of duty. That's Maroncelli on the front of the Greeley

Tribune the next morning, receiving the medal.

-- B-17 bombardier Armand Sedgeley of Lakewood, whose plane was hit and had to be ditched in the

Bay of Calvi.

Also, in a private meeting in conjunction with the ceremony, former Colorado State

University athletic director and U.S. Senate candidate Jack Graham accepted the medal for his late father, Joe Graham, a 781st Tank Battalion captain who essentially fought all the way across Europe. His

medal was in the works when he died in 2018.

Lemoine's French message was a mandatory part of his country's highest award, designated

in five degrees, and the Coloradans received the Chevalier, or Knight, version of the medal in the packed chapel at the Good

Samaritan Retirement Village.

In French, Lemoine told each one, per the prescribed

ritual: "On behalf of French president, and according to the powers given me, I bestow upon you the Medal of Chevalier

in the Order of the Legion of Honor."

The

medal can go to veterans who served on French soil during the war, fought off the coast, or flew missions on German targets

in France.

"It's very important to remember what happened," the Los Angeles-based Lemoine

told me after the ceremony. "It's very important to remember who came to liberate us and free Europe. It's important

to remember that the American Army was at that time engaged in liberating Europe. The Europe we have now and the France we

have now is thanks to them."

Lemoine

said he makes such presentations about once a month.

"We do remember the Greatest Generation and we remember what happened," he said. "Those

ceremonies are always very special for me as a French person. I was born in the '70s, but you see it and my grandparents went

through all of this."

The recipients were grateful, and friends and family

members scrambled for position to take pictures for posterity.

"This is a very special honor that I didn't really expect to see after 75 years," said

Bill Powell. "But I'm very, very thankful for the presentation, and also for the turnout here. It's wonderful."

Morrison, who served with the 118th Evacuation Hospital,

said simply: "I was just so thankful to serve. I was very thankful that I had the skills of a nurse, because I know we

saved lives."

She conceded it was an emotional day for her.

"A lot of memories," she said. "Some

good. Some bad."

I had profiled three of the veterans -- Bill Powell, Philip

Daily and Joe Graham -- in advance of the ceremony. I eventually caught

up with Harry Maroncelli later in February. Finally, I was able to check in with Leila Morrison after she returned from attending

the ceremonies commemorating the 75th anniversary or D-Day in June, and also tell her amazing story.

Former

colleague Kevin Simpson told Armand Sedgeley's story in a terrific piece a few years ago.

* * *

Leila Morrison in Normandy, signing the jacket of Best Defense Foundation program director

Ralph Peeters, who lives in The Netherlands. (Photo courtesy Ralph Peeters)

Leila Morrison is seventh from left (in white pants) among the Best Defense Foundation-escorted

veterans on Omaha Beach. (Best Defense Foundation photo)

On June 6, the 75th anniversary

of D-Day, or four months after the French Legion of Honor Medal ceremony, Leila Morrison looked out over Omaha Beach.

"I just couldn't

believe it," Morrison told me after returning to Northern Colorado. "It was so different from 75 years ago, when

we arrived. There wasn't anything recognizable except maybe the sand on the beach. It brought back so many emotions and everything

else you had inside of you."

Morrison is 97 and since 2010 has lived in Windsor, between Fort Collins

and Greeley.

This often is lost in the narrative, but Morrison (then known as Leila Allen) and other Army nurses

came ashore shortly after the D-Day landings and moved with the battle lines and the U.S. troops across Europe, working under

trying conditions in operating "rooms" that actually were triage tents. With the 118th Evacuation Hospital, she

witnessed both the carnage of battle and, at Buchenwald concentration camp, the results of the horrific actions of Nazi Germany

in implementing the unspeakable "Final Solution."

Morrison was the only woman among the 14 U.S. veterans of the Normandy campaign taken to France for the D-Day commemoration by the Best Defense Foundation, a remarkable organization

founded and run by former San Diego Chargers linebacker Donnie Edwards. The group sat behind President Donald Trump at the

official commemoration ceremony, and Trump introduced and hugged one member of the party, Russell Pickett, who as an 19-year-old

private in the 29th Infantry Division was among the first to arrive on shore, braving the German fire. French president Emmanuel

Macron helped Pickett stand.

"Today, believe it or not, he has returned to these shores to be with his

conrades," Trump said of Pickett. "Private Pickett, you honor us all with your presence."

Leila Morrison with French children

(Best Defense Foundation

photo)

Leila Morrison

was sitting nearby.

"There are very few of us left from World War II," she said.

"They told us while we were there that we were probably the last World War II folks who would be there for a public ceremony,

and it really was a big one."

The commemoration ceremony was the highlight

of the Best Defense Foundation's 10-day trip, which also took the veterans to Paris and other and other French cities and

sites.

"It was quite a trip, especially for an old woman," Morrison told me. "It's taken me longer to get

over than I thought. It was a schedule for a teenager. But we made it and I'm thankful I could. We were treated like royalty.

The French people respected us and gave us every courtesy possible. They were just happy to serve us. Even though it's three

generations later, the people seemed to really be willing to remember it and they're teaching their children about what happened.

We went to a couple of schools and the children really welcomed us and had made little banners. They seemed to know and understand

quite a bit about World War II."

The Best Defense Foundation, which takes veterans back to the sites of their combat, came across her story and invited her on the momentous 75th anniversary

trip.

She met the group in Los Angeles and they flew -- in First Class, thanks to upgrades from United Airlines -- to Paris

and eventually ended up in Normandy.

At

Normandy, Leila Morrison, center, is surrounded by

other Coloradans, from left: Julie Mann, Lilly Schroeder,

Brooke Moser, Quinn

Schroeder, Carrie Vaughn.

(Photo courtesy Marc Moser)

Activists who support Edwards include Jake Schroeder, who is the head of Denver's

Police Activities League and sings the National Anthem at Avalanche games; and Avalanche television broadcaster Marc

Moser. They have become close friends of Ralph Peeters, the Best Defense Foundation's Netherlands-based program director.

Both Moser and Schroeder were at Normandy for the 75th anniversary with their daughters and interacted with Morrison.

Morrison became beloved among Best Defense Foundation personnel and

charmed the young people meeting the American visitors.

"She was an inspiration and a lovely

lady to have on the program," Peeters told me. "She was an ambassador for all nurses who served in World War II."

Anna Beker, another

Foundation program director involved with the trip, said Morrison "was the sweetest and nicest person there. An absolute

angel! All the boys loved her!"

Raised in Blue Ridge, Georgia, Morrison entered the Army Air Corps

as a nurse after her graduation from nursing school in 1943. Her training was at Lowry Field in Denver and Santa Ana Air Base,

and then Camp Bowie in Texas. There, she was shifted to the Army and soon was commissioned as an officer. Also while

at Camp Bowie, she met a dashing Army officer named Walter Morrison at a dance and turned down his virtually immediate marriage

proposal, saying she couldn't get married while a war was raging. But they remained in touch.

She was

transported to Scotland on the coverted (and packed) Queen Elizabeth, went through additional training and briefly was stationed

in England before she was assigned to the 118th Evacuation Hospital. Then she and other nurses traveled on a British ship,

the Southhampton, to Omaha Beach.

Morrison said it was "a couple of months" after the D-Day

landings. The battle lines had moved on, but the goal was for the medical personnel in the unit -- including 40 doctors and

40 nurses -- to catch up.

"We could not come in very close, because of the

mines and sunken ships still there in the harbor," she said. "So we had to swing off this little, bitty ship on

this rope ladder. Some GIs were there in this little LST (Landing Ship, Tank) boat. I think that's the name of it. It opens

up in the front. We went in on that, and we walked out of it onto the beach. There was a two-and-a-half-ton truck there, and

that's what we toured Europe in, all the rest of the time. They took us down to a small town there in Normandy and then we

proceeded on to where the lines were to set up our hospital."

They moved through

France, Luxembourg (in the Battle of the Bulge), Germany and Czechoslovakia.

"It was all in tents,"

she said. "We lived in tents. The hospital was in tents. It was all a bunch of tents with a big red cross on top."

(That was to identify

it as a hospital, making it off limits for bombing under international law.)

In tents, the unit treated

the seriously wounded, hoping to get them alive to better facilities, usually station hospitals. Yes, think a M*A*S*H

unit -- but even more makeshift and more on the move.

"Our hospital worked like a big emergency

room," she told me. "We only took emergencies. If we thought a soldier would not make it back to a station or a

general hospital, we took them and brought them out of shock and stopped their hemorrhaging for surgery. We gave many, many units

of blood plasma. There was no preservation of whole blood at that time, so the next best thing was blood plasma. It was a

powder we had to mix with sterile water. We gave that to almost all of them."

When I asked her about following the battle lines, she responded: "Many times we didn't even know

where we were. It was a complete blackout, of course, and we traveled a lot at night. We'd say, 'Where are we?' And most of

us would say, 'Well, I don't know. Somewhere in Germany or somewhere in France.'"

Eventually, they arrived at Weimar, Germany and the site of the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp.

It had just been liberated.

"Some things I didn't believe," she said. "We pulled

into the town and set up our tents and we were told that we would be moving on the next day. Then they told us that evening,

'Buchenwald is just across the stret here, you could walk over there,' They said, 'You girls be ready in the morning because

we're going to have to go down there and help out.' The next morning, we were ready to go and they came and said, 'You girls

can't go today. The doctors are already down there and the conditions are too deplorable for you girls. You have to wait until

tomorrow.' So that's what we did.

"The next day we went down and they had it cleaned up -- I guess

that's what you would call it -- to a certain extent, and we saw things that I still hav a hard time believing. The poor people."

They saw the crematorium,

stacks of bodies and emaciated survivors.

"The crematorium, they had it worked out like a factory of murder,"

she said. "It was a two-story place and they had eight ovens on each side of this brick crematorium."

After Germany's

surrender and and after returning to the U.S., Morrison was told she would be deployed in the upcoming invasion of Japan.

But that nation surrendered in August 1945.

The storybook wartime romance had a happy ending. Leila married Morrison,

who served in George Patton's U.S. Third Army. They were married for 65 years before Walter's death. Leila was a civilian

nurse for 30 years, and she came to Windsor -- and the Good Samarita home, where the French Legion of Honor Medal ceremonly

was held -- from Georgia to be near her son, Wally, and his family.

For many years, Morrison

said, she didn't talk much about her wartime experiences with anyone but he husband.

"The two of us could

talk about it and understand," she said. "But just didn't talk to other people about it," she said. "I

hear people say, 'Oh, my grandpa served, but he wouldn't talk about it.' We didn't either, for years. We had two daughters

and a son and my daughter asked years later, 'Well, Mom, why didn't you tell us some of it? You never mentioned it to us.'

It was all such a horrible thing and my husband and I could talk to each other. He understood. We had an outlet for the two

of us because we could share it."

Leila Morrison is third from left in this shot from the May 2018

Honor

Flight Northern Colorado trip to Washington D.C. She's with

four women veterans from

the Vietnam War era and one from the Korean War era,

The past 13 months have been dizzying for Morrison. She was one

of 123 veterans who were part of the Honor Flight Northern Colorado trip to Washington D.C. in May 2018, the next-to-last

trip for that organization before it shut down in the wake of the death of Col. Stan Cass, its founder and organizer, then

was rebooted as High Plains Honor Flight.

Next, in a February ceremony at her retirement home in Windsor, she was one of six World War II veterans with Colorado

connections who received the French Legion of Honor Medal for their service in Europe.

Other members of the Best

Defense Foundation group received the medal while they were in France.

Honoring Morrison and the others was part of a labor of love for Donnie Edwards and the Best Defense Foundation, who earlier in the year escorted a group of surviving veterans to Iwo Jima.

Donnie Edwards on Omaha Beach with vet Pete Shaw

(Best

Defense Foundation photo)

The group also visited cemeteries and laid wreaths. But it all came back to Omaha Beach, the focal

point of the trip.

"When we first pulled up, I looked out there at that big ocean," Morrison

said. "It was a cloudy day. The wind was blowing. I thought, 'Oh, my goodness, how in the world did I ever have nerve

enough to swing off the side of that ship?' I just couldn't believe I had done that. Of course, 22 years old and 97 years

old makes a little bit of a difference there."

Leila Morrison with fellow veteran Pete Shaw at Normandy

(Best Defense Foundation photo)

At

the Eifel Tower, Leila Morrison is seventh from left.

(Best Defense Foundation photo)

Leila Morrison and the other veterans on the Best Defense Foundation Trip at an

elementary school in Carentan. (Best Defense Foundation photo)

* * *

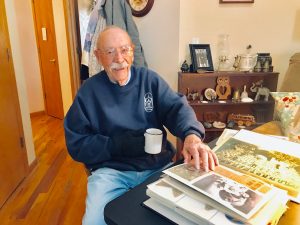

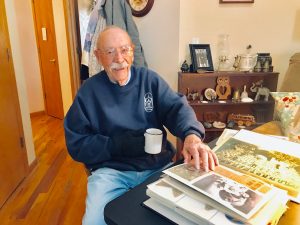

Bill Powell in Fort Collins

When I

visited 97-year old Bill Powell in Fort Collins, the front of his hat bore the drawing of a B-24 bomber and its "Liberator"

nickname. His interest is more than that of an aviation enthusiast. As an Army Air Forces pilot, Powell flew the four-engine,

twin-tail bomber from the left-hand seat, commanding a crew of 10 others.

Later in the day, when I spoke with 93-year-old Philip Daily in his Brighton home, Daily donned

the generic "World War II veteran" hat that was sitting on his couch. (Actually, he put it on because I asked him

to, for a picture.) As a cramped tail gunner on a B-17 "Flying Fortress," Daily's job was to fire from the back

of the plane in the case of attack from fighters.

Different planes, different jobs, same cause.

When their planes were hit during bombing raids, they managed to bail out and parachute to the

ground, only to end up in separate German Stalag Luft prison camps. Daily went through what for many American prisoners was

the deadly forced mass march. Powell was fortunate enough to avoid that.

Powell

was raised 30 miles west of Cleveland, in Elyria, Ohio. He was attending Ohio Northern University when he enlisted in February

1942. He was called up late that year.

After

flight training, he and his crew ended up in Cerignola, Italy.

The crew's first nine missions, beginning in August 1944, were fairly uneventful. Three of them

were supply missions to Lyon, France, where Allied forces had captured the German-controlled airfield.

Young pilot Bill Powell

Then came No. 10, in October 1944. Powell's B-24 was part

of a tight, four-plane formation on a huge mission.

"The mission was to bomb the railroad marshaling yards at Munich," Powell said. "We came

off the bombing run and I turned the controls over to the co-pilot."

He stood up. That was typical strategy because of the strain on the pilot during the bombing run.

"I looked out through the windshield and here came

two 500-pound bombs from up above," he said. "They hit the left wing of the lead ship and I was flying right behind

him."

Powell's guess is another plane's bombs got hung up

and released late at an inopportune time and spot, essentially becoming "friendly fire." Shrapnel from the struck

lead ship tore into his plane. His co-pilot was hit and killed immediately. Powell's headrest was blown off. If he had stayed

in his seat, he would have been dead, too.

He

grabbed the controls. His control of the plane was marginal, and two engines were out.

"I felt the condition of the ship was such that we probably wouldn't make it back

across the Alps," he said. "So I gave the order to bail out. I hit the ground and turned around and started to take

my chute off and looked up and here was this German farmer holding a pistol on me. He motioned me to pack up my chute and

come with him."

Powell ended up in a central interrogation station up

in Frankfurt.

"I realized during the interrogation that I had

only been in the squadron six weeks and the Germans knew a hell of a lot more about the squadron than I did," Powell

said.

The next stop was Stalag Luft I, on the Baltic Sea near

Barth, in northern Germany. Conditions were Spartan, dirty and crowded. The food - mostly potatoes, cabbage and turnips, cooked

by the prisoners themselves - was awful, beyond occasional Swiss Red Cross parcels. Yet the Germans essentially left the prisoners

on their own outside roll calls. At the camps, Americans were ingenious at coping, even playing football, softball and - improbably

- ice hockey; staging concerts and plays; publishing one-page newspapers; and using clandestine radios to follow the war news.

"The rest of the time, you stayed in your room,

or walked around the complex for exercise," Powell said.

As Russian forces closed in from the east and American forces moved in from the west, plans were

formulated to force the prisoners to march under horrendous conditions to another camp. That's what was going on at other

camps. But eventually, the German commandant and senior U.S. officer agreed the Germans simply would abandon the camp, leaving

the prisoners on their own.

The Russians arrived. The camp was liberated. Powell

had been a POW for seven months.

After

returning to the U.S., he got married, and he and his wife, Norma Jean, soon heard of Japan's surrender, ending the war.

He finished college at Ohio Northern and went to work

for the Miami-Dade County public works department in Florida. He eventually became director of public works for 10 years before

his retirement. Officials in 1986 named the final project of his tenure - the bridge linking Miami and Key Biscayne - the

William M. Powell Bridge.

His daughter, Barbara Vowles, went to school at Colorado

State University in the mid-1960s and remained in Fort Collins, so in retirement Bill and Norma Jean bought a home in Fort

Collins and went back and forth. Norma Jean passed away in 2003, and Bill still lives in the house they had built.

* * *

Philip Daily at his Brighton home

Young Philip Daily's family lost its farm near Akron, Colo.,

in the Great Depression and moved to Brush. Philip worked at grocery stores to help out the family and also hunted game and

fished to supply food.

"My mom would cook anything we brought home,"

he said.

Daily ended up attending what now is the University

of Northern Colorado in Greeley, working in the campus cafeteria and in a local store. He enlisted in the Army Air Forces

and was called up in December 1943.

"They

found that my vision was no good, so I couldn't be a pilot," Daily said. "So I was sent to gunnery school at Las

Vegas."

As a staff sergeant and gunner, he ended up on the B-17

crew stationed at Foggia, Italy. He was 19.

"In

those days if you flew in the Balkans, you got credit for one mission," he said. "If you went north of the 38th

parallel into Germany, you got credit for two missions."

Young Philip Daily

Daily's 25th mission, on Oct. 12, 1944, was a run over railway marshaling areas in

Bologna, Italy. The Germans had huge anti-aircraft artillery guns in place on the ground.

"All that time, we hadn't seen one (German) fighter because the war was tapering

off," he said. "It had never bothered me seeing flak out there. But that day we got hit by anti-aircraft fire. When

you looked out, three of the engines were out and we were on one engine. We started going down."

He made it out.

"When I got close to the ground, two guys were coming up the hill," Daily said.

"One had a rifle and the other guy had a pistol.

They had told us that it was possible the Resistance might pick us up. When I hit the ground, I asked them, 'Italians?' They

said, 'No, Germans.'"

Soon, he was at Stalag Luft IV in Gross Tychow, Poland.

He was the 21st POW in a barracks with 20 beds, so he had to sleep on a table. The conditions were similar to those at other

Stalag Luft camps, including Bill Powell's Stalag Luft I, with the prisoners trying to make the most of horrible potatoes.

"At least we ate," Daily said. "And that's

where I learned how to dance. We had a rec hall and one of the instructors from Arthur Murray's was there."

On Feb. 6, 1945, the order came for about 6,000 POWs

- Daily included - to leave the camp and march under guard to the west, through often horrible weather and miserable conditions,

including frequent violent treatment from the German guards. POWs falling behind sometimes were shot. It came to be known

as "The Winter March." Many were ill.

"They

broke us up into groups of around 200," Daily said. "We'd walk all day and then we'd go in a farmer's barn at night

and sleep."

They covered 15 to 20 miles per day. In late March,

the march ended near Hanover and the survivors were loaded on boxcars and taken to Stalag Luft 2B for enlisted men, but Daily

and the Stalag Luft IV men didn't stay there long. They were sent out on another march, going back over ground they already

covered.

They were near Hamburg when they awakened May 2, 1945.

"Lo and behold, the German guards were gone." Daily said. "About a half-hour later, here come the British."

Over the 86 days and 600 miles, about 1,300 American

airmen died.

Daily

had severe dysentery and wasn't able to eat solid food for many years after the war.

After attending the University of Colorado, Daily settled in Denver with his wife,

Jeanette, and became a salesman of various wares. He ended up in Brighton, owning Daily's Appliance Store until the early

2000s. Jeanette died in 2016.

Daily and Bill Powell both passed through the same transition

camp for liberated American POWs in France, dubbed "Lucky Strike." They didn't encounter each other there, but they

had met several times before the French Legion of Honor Medal ceremony.

"It kind of was over for about 20 years before it kind of started to get recognition,"

Powell said. "It's always a little surprise when somebody says, 'Hey, come on, we're going to give you a party."

*

* *

Harry Maroncelli at his Fort Collins home

I visited Harry Maroncelli at his Fort Collins home. Near

the end of our hour-long conversation, I finally got around to his reaction to receiving the Legion of Honor medal.

"Oh, I think it was one of the most eventful happenings in my life," Maroncelli said.

"I really appreciate the French thinking enough of the kids that were over there, helping them get back their freedom.

I really think it's great. And I think all of us, in our hearts, we're not taking this medal for ourselves. We're thinking

of the guys we left behind. And we did leave an awful lot of guys behind."

Harry made it through an entire tour of duty, which by that time was 35 missions, flying

out of Deenethorpe, England. Amazingly, he never had to fire his gun. By that stage of the war in Europe, German forces were

diminished. That doesn't mean the B-17 crews didn't face danger. They did, from notorious German 88 mm anti-aircraft guns

on the ground and also remaining German fighters. But the young crewman from the Bronx, north of Yankee Stadium, couldn't

do anything about that. Except hope and pray.

"Where

I grew up, you could call it the Little Italy of the Bronx," he said. "It was all centered around Arthur Avenue.

That's the place to go when you want legitimate, original, best Italian food."

Harry went to elementary school at Our Lady of the Angels and then DeWitt Clinton High

School, also walking 65 blocks north to work his Bronxville News delivery route.

After his 1941 high school graduation, Maroncelli went to work for a financial bookkeeping

firm in Manhattan.

Then the U.S. entered World War II, he signed up for

the Army Air Forces.

"Growing up, I had ideas of being a pilot,"

he said.

When he was called up for induction in late 1942, he

took the typical physical stress test designed to measure an inductee's physical suitability for pilot duty. "It was

called the Schneider Test," Maroncelli said. "I flunked. If you just think about it, here's a kid 18 years old,

and gets flunked for having a bad heart. Now, at 94, I have to laugh."

Young Harry Maroncelli

His path to becoming a ball turret gunner was circuitous.

After he went through basic training at Atlantic City, he was trained to be a mechanic for Douglas A-26 Invader light bombers.

That training was in East St. Louis, adjacent to the Pratt & Whitney engine plant, and he was certified as a mechanic

for the A-26 in mid-1943. As he was about to ship out to a base in Florida, he was yanked from the mechanic unit, taken to

a Navy base and given the pilot suitability test again.

"The sailor said, 'Harry, you're going to pass this test before you leave here,'" Maroncelli

said. "And I did. Whenever the figures were right, he put them down."

He ended up placed with a group of air cadet recruits in Missouri and went through

basic training again. "I was a little bit bewildered," Maroncelli said. "I had corporal's stripes by that time,

after B-25 training."

When he was left behind as the others shipped out, and

he went down to a headquarters and asked what was going on. "Somebody forgot to punch a hole in an IBM card," Maroncelli

said. "The whole world was operating on IBM cards and until the right holes were punched, you didn't move. So I got somebody,

I think, to punch that hole for the next shipment."

He ended up at Washington University in St. Louis, attending classes and flying 10 hours in a Piper Cub

trainer. "By the time I finished those 10 hours, I knew I wasn't going to be a pilot," he said. "I just didn't

and don't have eye to hand coordination and depth perception for that."

He went into the aerial gunnery school in Laredo, Texas. There, on the firing range with a rifle,

he didn't hit anything, then heeded his instructor's order to switch the rifle to the other shoulder. Voila, he discovered

that he had been doing it all wrong, and that his master eye was his left, not his right, eye.

He was assigned as a ball turret gunner, with a B-17 crew training in Sioux City, Iowa.

Then it was off to Europe, joining the 8th Air Force's 401st Bomb Group, 615th Bomb Squadron in Deenethorpe. A remarkable

615th Squadron History by Vic Maslen, a 179-page typewritten manuscript, provides many details of the squadron's missions.

There are some missing because of gaps in the microfilm.

With L.E. "Coop" Cooper as the pilot, Maroncelli's crew flew its first combat mission on Aug.

8, 1944. It was a 43-plane trip to Hautmensil, France, near Caen in Western France, to support Allied ground troops. This

was two months after D-Day and the landings at Normandy.

"We were bombing ahead of them," Maroncelli said.

On that first Maroncelli mission, the 615th contributed 10 of the planes, and one was shot down,

with four crewmen going down with the ship.

"I

never had any fear," Maroncelli said. "I can't figure that out. I was always sure I was going to come back.""

The Cooper's crew's next missions were to Luxembourg,

Brest, Schkenditz, and Terte/La Louvierre. And then, on Aug. 27, it headed for Berlin, but bad weather forced the 615th's

planes to turn back. It was on to Coubronne, Mannheim (twice), Gaggenau, the I.G. Farben oil plant at Merseburg (twice), Groesbeck,

Hamm, Kassel, Nuremberg, Stargard, Politz, Hanover, Hamburg, Munster, Frankfurt, Harburg and Merseburg.

Then on Dec. 5, 1944, Cooper's crew headed back to Berlin.

Maslen's history noted it "was a strange experience for the crews to fly over

Berlin and find that the flak was meager and inaccurate." But he also noted that the 17 fighters were lost in the mission,

and that the U.S. planes shot down 91 German fighters.

After that, the Cooper crew's missions were to Merseburg (again), Koblenz, Gerolstein, Rheinbach, Bingen,

Kaiserslauten and Kassel.

From the spherical shaped ball turret attached to the

bottom of the plane, Maroncelli's scariest moment was seeing a friendly P-51 fighter plane shot out of the sky by flak.

"He blew up right in front of me," Maroncelli

said. "This guy was escorting us and we were safe. He just disappeared."

Maroncelli remains flabbergasted that he didn't have to fire that gun. He also notes

that on one long mission, the heat to the ball turret malfunctioned and he had to take great care to avoid frostbite. "I

was bringing one foot at a time into my lap and pounding it with my fist to keep the circulation going," he said.

His 35th and final mission, he said, "was what

we called a milk run."

And he was done.

He returned to the U.S. and volunteered for training in B-29 bombers, anticipating

a continuation of the war in the Pacific Theater against Japan. But after the August 1945 end of the war, he left the service

the next month. He got out quickly on a points system, based on his time in combat and his Air Medal with a silver leaf cluster,

meaning he won the medal five times.

After

graduating from Columbia University in 1949, he had a long career as a salesman, trainer and manager for the Yellow Pages,

living in Pleasantville, N.Y. Many years following his retirement, the widowed Maroncelli finally heeded the suggestions of

his son, Rich, who had moved to Fort Collins in 1982 and was working for Hewlett Packard. Harry purchased his Fort Collins

home and came to Colorado in October 2013. He lives with his partner, Beckie Wagner.

Harry turned 95 a few days after our conversation.

* * *

Joe Graham

Sadly, the Legion of Honor medal was in the works for several years was in the works

for former 781st Tank Battalion captain Joe Graham, before he died at age 100 in Palo Alto, Calif., in the summer of 2018.

The plan had been for Graham to come to Colorado to

accept the medal, and he had also journeyed here in 2013 to be a part of the Northern Colorado Honor Flight trip to Washington

D.C.

But his son, Jack Graham, accepted the medal for him.

Proudly.

Joe Graham's Europe tank duty, in Sherman "Easy Eight" upgrades on previous larger models,

took him and the 781st to France, Italy, Germany and Austria in what largely was an unrelenting fight. As a captain, Graham

led Company D.

"The thing that Ginger [Jack's wife] and I were

hoping for more than anything was that he would have been awarded the medal while he was living and while he was healthy,"

Jack Graham told me. "His health really started to fail, I would say, at the beginning of 2018. It's OK. 'Pop' knew he

was getting the award and he was thrilled by it. The fact that he never got handed the award is kind of secondary. He was

proud of it."

What will it mean for Jack to accept the medal?

"It'll he hard," Graham, 66, said. "That

part of my dad's life, the four years he spent in the Army, were far and away the most important and defining years of his

life. For a kid out of Brooklyn, N.Y., who literally didn't know one end of a wrench from another, to become captain of a

tank battalion and fight the kind of fight that he had to fight is such a testimony to who he was as a leader and to his toughness.

I'm not talking about physical toughness. My dad was a tough guy, but he was mentally tough and disciplined. There was nothing

he couldn't do if he set his mind to it.

"He

was asked to do things that were so far out of his knowledge base, and he still did them really well. To me, it's almost another

chapter of his life. If this is his book, it pretty gracefully ends the book."

The point is, the World War II generation is leaving us. It won't be long until all

veterans of that era are gone. It took a disgraceful amount of time for those of us among their offspring to fully grasp and

appreciate their contributions, but part of it was that for so many years, it just was a given. A matter of fact, a checkmark,

a line on a list of accomplishments.

World War II veteran.

And

so many of them shrugged, accepted, it even wanted it that way.

Hadn't it seemed as if they all had done it, regardless of whether that meant horrific combat

or never experiencing battle?

Eventually, we caught on. In some cases, it was too

little, too late.

Jack Graham began speaking more with his father about the war after Joe's wife and

Jack's mother, Janet, died in 1997. Joe was despondent. Jack challenged him to write his memoirs. They ended up at the Smithsonian

Institution.

"My dad and I spent countess hours toward the end

of his life talking about what he did in the war," Jack said. "He had a graphic, vivid memory of everything that

happened. Obviously, that kind of experience is going to mark you indelibly. It did Dad. And he said to me two or three months

before he died that they went seven months without stopping. Seven months. And they fought every single day. When he told

me that, it hit me between the eyes. I cried like a baby.

"When somebody says something like that, you kind of go 'wow.' You think about what that life experience

must have been. Misery. What those guys had to experience. What they had to sacrifice. To go seven consecutive months without

a day off. A day off from war is kind of an oxymoron, obviously, but they went seven straight months, never sleeping indoors,

sleeping under their tanks in the dead of winter. My god, the sacrifices. It bowled me over."

Joe Graham was born and graduated from high school in New Jersey before the family's

home was repossessed during the Great Depression and they moved to the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. After nine months of

trying to land a job to help support the family, Joe jumped at the chance to be an office boy at Travelers Insurance, at $15

a week, and enrolled in night classes at New York University.

His Travelers bosses told him he would not be promoted, get a raise or be retained beyond two

years. That was how the Great Depression worked.

He

got them to change their minds: He was all the way up to $27.50 a week when he was drafted in September 1941, three months

before the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into the war.

He had never driven a car.

His brother, Walt, joked that meant he would be assigned to a tank unit.

And, of course, he was.

Joe Graham graduated from Armored Officers Candidate School in early 1943 and was anointed a 2nd

Lieutenant, eventually to become a captain.

A tank from Joe Graham's 781st Tank Battallion in France

The

781st Tank Battalion landed in France in 1944. Supporting the 100th Infantry Division, Graham and the 781st was in the Battle

of the Bulge, the Battle for the Rhineland, the Battle for Southern Germany, and the Battle for Po Valley.

Graham came out of the

war with a handful (or chest full) of medals, including the Bronze Star and the Army Medal of Commendation.

After his discharge, Graham joined Insurance Company

of North America and stayed with the firm until his 1980 retirement. Eventually a high-echelon executive and the president

of a struggling INA subsidiary he nursed back to financial health, Graham was based at New York, Cleveland, Indianapolis,

San Francisco and Los Angeles, and retired to San Luis Obispo until moving to Palo Alto following his wife's death.

His son, Jack, was a CSU quarterback in the early 1970s

who then made a fortune in the catastrophic risk insurance business and sold his company. As a CSU booster living in Boulder,

he was frustrated when approached to contribute to a Hall of Fame project in Moby Arena and instead asked CSU president Tony

Frank for permission to let him attempt to raise money for what he labeled a true difference-maker, an on-campus football

stadium.

Impressed with Graham's vision and audacity, Frank talked

him into becoming athletic director. The stadium was Graham's vision and his baby. Frank did much of the public campaigning

and lobbying of the CSU system's board of governors before the project was approved in late 2014, but he and Graham - both

strong-willed - had a falling out that led to Graham's firing in August 2014. Graham, the successful businessman, had little

patience with the frequently cumbersome red tape of academia and didn't try to hide it.

Since leaving CSU, Graham staged an unsuccessful run for the 2016 Republican nomination

for the U.S. Senate seat eventually retained by Democratic incumbent Michael Bennet. He and his wife also have the "Ginger

and Baker" restaurant in Fort Collins. Finally, the Grahams purchased additional land around the couple's home near Fort

Collins and now have horses; next they will add cattle to the 200-acre spread in October. Jack has become a gentleman rancher.

"I'm thoroughly enjoying that, doing physical labor and not sitting behind a desk," he said.

When I asked Jack if one of his father's stories about that seventh-month advance stood

out, his answer surprised me. It was not about valor. It was about what war is. It is hell.

"It's not a good one," Jack said. "They were moving and they were on

a road on top of a dam or levee. It was a one-lane narrow levee road and Pop was in front in a Jeep. They saw some Germans

coming towards them in some armored personnel carriers. The Germans could see that there was a line of tanks behind my dad.

So they bailed. They got out of their vehicles and took off running through a pasture.

"Dad got down and ran toward them and got what he called a Tommy Gun. He was spraying

them. He shot a guy and he came up on the guy and the guy was ..."

Graham's

voice broke and he paused.

Then he continued.

" ... the guy was 14 years old. The guy died in my dad's arms."

Graham paused again. "Sorry, I have to pull it

together here."

He continued. "My dad told me, 'That's the first

time I've told anybody that story.' So it was cathartic. And you can imagine how how hard that would be to live with. My dad

spoke fluent German. His mother (born Elizabeth Kotzenberg) was German. The kid was crying for his mother. He and my dad spoke

to each other."

If only we lived in a world where medals weren't necessary.