HOMEInstitutional Knowledge commentariesBioFilm rights, Screenplays, RepresentationOlympic Affair: Hitler's Siren and America's HeroTHE WITCH'S SEASONThird Down and a War to GoHORNS, HOGS, AND NIXON COMING'77: DENVER, THE BRONCOS, AND A COMING OF AGEMarch 1939: Before the MadnessPLAYING PIANO IN A BROTHELSave By RoyA Selection of Terry Frei's writing about World War II heroesThe OregonianThe Sporting NewsDenver PostESPN.comGreeley TribunePress CredentialsThey Call Me "Mr. De": The Story of Columbine's Heart, Resilience and RecoveryOlympic Affair: Chapter 1, Leni's VisitOlympic Affair: Chapter 15, Aren't You Thomas Wolfe?The Witch's Season Excerpt: Air Force Game, Bitter Protest, a Single ShotThird Down and a War to Go genesis: Grateful for the Guard, Jerry FreiHoneymooners Meet the Boys of SummerTommy Lasorda, the Spokane Indians, and My Summer of '70Smoke 'em inside: On Ball Four and Jim BoutonEarthquake at the World SeriesMosquito BowlA Year with Nick Saban before he was NICK SABANJon Hassler, Terry Kay and other favorite novelistsKids' sports books: The ClassicsBig Bill Ficke's Big HeartBob Bell's Food For Thought

|

| |

In this adapted excerpt from '77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age, I tell the stirring tale of how the Broncos got to the Super Bowl for the first

time by beating the Raiders in the AFC championship game on New Year’s Day 1978. As related in the book, under first-year coach Red Miller, Denver was coming off a

stunning 12-2 regular season record and then a 34-21 win at Mile High over the Pittsburgh Steelers in the first round of the

playoffs on Christmas Eve. But veteran quarterback Craig Morton, brought in off the scrap heap through a trade with the New

York Giants, had been having problems with a hip pointer that evolved into something worse. The bleeding in the area didn’t

stop and he came out of the game against the Steelers banged up, plus black and blue. Picking up the story from there… Miller told reporters on Monday — the day after Christmas, the day after he had to spend part of his morning

taking down a “Broncos Are No. 1″ banner fans had strung between trees in his front yard — that Morton had

received treatment at St. Luke’s for his sore hip and leg, but the coach was adamant that Morton would practice during

the week and play. Actually, Morton visited the hospital Sunday

and checked in as a patient on Monday. It was a miracle the extent of his plight and his continued hospitalization remained

secret. Maybe the “smart money” got wind

of Morton’s status, though: The Raiders opened as 3 1/2-point favorites in the Nevada sports books, and the

line stayed there. At the time, linebacker Tom Jackson put

it this way: “Everybody and anybody who’s ever been an underdog will be rooting for us. They want to see Cinderella

get her slipper back. They want to see the sheriff come in and clean up the town. Ever since I learned we were going to play

Oakland, I’ve been wondering where the edge was going to come from. The edge came from the bookies.” If the number seemed out of line, serious players and large bets would have forced

it to move. It didn’t. So it wasn’t the bookies. It was the bettors. There was a tendency to wonder how the Broncos,

in their first-ever trip to the playoffs, could handle the pressure and whether the defending-champion Raiders’

karma could win out over the franchise that sometimes seemed like an intruder on the national stage. Plus … Pssst.

Hear about Morton? Looking back, Morton told me, “My

leg was like two, three inches bigger, full of blood. It was red and purple. It was huge. So they came in all the time at

the hospital and tried to drain blood from it.” That

didn’t do much good. When the Broncos went back to work

on Wednesday, Miller closed practice to the media, a bit eyebrow-raising at the time. The coach explained to reporters: “We

want to be accommodating, but we want to be able to keep our concentration, too. It’s not that we want to try to hide

anything in the way of gimmicks or anything like that.” He

avoided mentioning injuries. Miller

did say that Morton was held out of practice but added the quarterback would be back in pads on Thursday. He didn’t

mention that Morton still was in St. Luke’s, or that he had visited the quarterback that morning. “He brought

me the gameplan,” Morton recalled. “So I studied the game plan. There were some wrinkles in there, some things

with Haven [Moses].” On Thursday, Miller again reported

that Morton hadn’t participated in pads, but at least implied that the quarterback had been present, in shorts and had

thrown the ball. On Friday, Miller told the media mob, including many national reporters who had arrived in town, that Morton

hadn’t joined in the non-pads workout that day, either. Still, no mention was made of Morton’s hospital stay. “I feel bad because it was a lie, but for no other reason,” Miller recalled.

“Craig wasn’t only black and blue. He was black, not black and blue, from here to here,” he said, making

a gesture that covered his entire side. Backup Norris Weese

took almost all the snaps that week in practice. Haven Moses told me later that the players had a tacit agreement not even

to talk about Morton’s health among themselves. “Nobody asked,” Moses said. “It was ‘don’t

ask, don’t tell,’ because we were trying to keep it away from Oakland that Craig hadn’t practiced all week.

We didn’t realize how bad he had been hurt, or how bad his leg was.” A former California teammate of Morton’s, Loren Hawley, was staying at Morton’s

house. “He came and got me [at St. Luke's],” Morton recalled. “He said, ‘What do you think?’

I said, ‘I don’t know. I can’t even walk.’ He said, ‘You’ve worked too hard not to play.’” Morton said Hawley took him right from the hospital to the stadium, where he first

spent a long stint in the whirlpool. He added, “I went out and walked around with sweats on. I found I could back up

fairly well, but I couldn’t move forward, couldn’t plant. So I went in and started getting dressed. I wanted everybody

to see that if I was going to play, they couldn’t hit me. It looked like it was gangrene.” His teammates marveled that he was even going to give it a try. “We’d heard

all the rumors, and he hadn’t praacticed,” guard Tom Glassic recalled. “But I didn’t know how bad

he really was until I saw him with his clothes off, and I saw him with all his bruises.” Receiver Haven Moses, the other half of the M&M Connection with Morton, recalled: “When I saw his leg, I said to myself, ‘Man, I’m surprised they didn’t

cut that sucker off.’ I had never seen anything like that. Deep, dark black.” Tackle Andy Mauer played the left side and protected Morton’s blind side. Seeing Morton

reminded him how serious that responsibility would be against the Raiders. “He looked like he had been in a car

wreck,” Mauer told me. Miller recalled approaching Morton

and asking: “Well, Craig, what do you think?” “I

said, ‘Coach, tie my shoes, I’ll play,’” Morton recalled. “So he got down in front of everybody

and tied my shoes.” The coach watched Morton make his

first throw in the warm-up. It was a labored, slow-motion, wincing toss. Miller said he turned to Weese and told him: “Norris,

get ready.” Yet the coach noticed that Morton started to loosen up, wasn’t wincing quite as much, and he was throwing

the ball with more authority. Back in the locker room after

the warmup, Miller approached Morton. “How do you want to do it?” he asked. That was the moment of truth — and for truth. Miller recalled the subsequent exchange this

way: Morton: “Well, let me start and I’ll tell

you if I can’t go.” Miller: “That’s

good enough for me.” But Miller also told Weese to warm

up as if he was going to play. Meanwhile,

star inside linebacker Randy Gradishar was wondering how his injured ankle would hold up. “I don’t think I practiced

on Wednesday, and it was still swollen,” he told me. On the first series of the game, though, he shot through and made

a tackle on the Raiders’ Clarence Davis and decided he was going to be all right. Or at least be able to get by. Morton, though, didn’t get off to a promising start. “I think the first

pass I threw hit Jack Tatum right in the chest, and he dropped it, which was unfortunate,” Morton recalled. Utimately, Morton connected with Moses five times, for 168 yards and two touchdowns

in the landmark game. The first M&M Connection touchdown

went for 74 yards in the first quarter, and it held up for a 7-3 halftime lead for the Broncos. Morton recalled that it came

after he told himself not to throw over the middle, or toward Tatum, again, and after he pretended not to understand a play

sent in from the sideline and called something else. “I said, ‘Don’t go in there any more, Haven, go to

the corner,’” Morton said. “So he did and I saw Haven running down the sideline and I said, ‘This

is going to be our day.’” Recalled Moses: “I

was on the east side, coming in motion toward the formation. Halfway through the motion, they snapped the ball and I went

upfield. Skip Rogers was the cornerback and I felt I had him beat. I wanted to hold him on my hip as long as I could, and

when I got to that mark where I wanted to go [toward the sideline], I gave him the hip fake because because we had been running

‘in’ patterns against Oakland he whole year. So he was anticipating the ‘in’ pattern, and I gave him

the hip fake and broke out to the corner. I didn’t know where the ball was, but I looked up and here it was coming.

I said, OK, catch it, and I was heading straight out of bounds. But when I caught it and I looked down, I was a long ways

from being out of bounds. Skip was reaching for me and he thought he was going to push me out. Just as I got to the sideline,

I said, OK, turn up, and momentum got me going up and I started hauling for the end zone. I looked back and I’m thinking,

OK, OK, there’s a flag somewhere. I think the last three yards I backed into the end zone and I didn’t see a flag.

We had a long way to go. But if you think about a game plan, with him not being a part of practice all week, for him to call

that play, there was a confidence factor between him and me.” With Denver holding that 7-3 lead in the third quarter, Oakland’s Clarence Davis fumbled at the Raider 17,

and Broncos defensive end Brison Manor recovered. Moments

later, Morton hit Odoms for 13 yards to put the ball on the 2. Then

came the most famous — and certainly controversial — play of the game. On first and goal from the 2, Broncos halfback Rob Lytle, the rookie from

Michigan, went off the left side, was hit by Jack Tatum, lost the ball, and Oakland’s Mike McCoy — of course,

the defensive tackle from Notre Dame, not the younger man of the same name who now is the Broncos offensive coordinator —

recovered and took off the other way with the ball. But

hold on… Linesman Ed Marion ruled that Lytle’s

forward motion was stopped and the whistle had blown before he fumbled. Replays, though, seemed to show he fumbled the second

he was hit, before he was knocked back. There’s a story

here, and it didn’t come out after the game. First of

all, when I asked him to go through the “fumble,” Lytle asked, “What fumble?” We both laughed, and then he explained. “Honest to God, I don’t even remember the play,” he said. “I told you what happened

to me the week before. [He was nailed in the Pittsbugh game.] So I must have had a bad concussion. I had headaches and stuff,

but those were the days that you didn’t … well, it was a different era. You didn’t think anything of it.

I didn’t play after that in the Pittsburgh game. They must have known enough to do that. I was out. “But the following week, we’re down on the goal line again and we run pretty

much the same play again I scored on [against Pittsburgh]. I went over the top and Tatum hit me. I can’t tell you other

than what I see on film, because I was out. You get one hit, and another good hit to knock you out is that much easier, you

know. I was out. “The only thing I know that happened

is that when you’re out, you go loose. The ball just stayed on my stomach. If they have instant replay, it’s their

ball. But in that day there’s no way those referees could have seen that. I ended up landing on it but I was out cold.

I wasn’t grabbing at it. As soon as I was hit, it probably squirted out a little bit and they were able to recover.” After the Broncos retained possession, fullback Jon Keyworth ran one yard for a Broncos

touchdown on the next play, and the Jim Turner conversion gave Denver a 14-3 lead. Moses had three more catches. His final one, and his second touchdown, came on

a diving catch that went for 12 yards in the fourth quarter, leaving the Broncos up 20-10 after Turner inexplicably missed

the PAT. “Craig had read from right to left, from

that side through Riley [Odoms, the tight end] and then to me,” Moses said. “He was just standing in the pocket,

just trying to buy sometime, and he came back to me. He threw the ball low, and I was stumbling into the end zone and couldn’t

get traction. Lester Hayes was on me and Craig threw it the only place he could throw it — down low. I was stumbling,

my feet were going down ande I looked like the Roadrunner, with everything spinning and getting no traction. It came right

in the basket and I caught it, and the only regret I have from that game is that I threw the ball up in the stands. Somebody’s

got that ball!” Ken Stabler’s second TD pass of

the game to tight end Dave Casper with 3:17 left got the Raiders back within striking distance, and it was 20-17.

The Raiders had two timeouts left and kicked the ball deep. Morton came on the field and told his offensive teammates:

“If we get two first downs, we go to the Super Bowl.” They

got them on a couple of clutch runs by fullback Lonnie Perrin and tailback Otis Armstrong. Otis’ run came behind tackle

Claudie Minor. “I remember Otis sticking his hand out of that pile of people,” Minor recalled. “He was holding

one finger, the number one, in the air.” The final seconds

ran off the clock. Denver won 20-17. Minor remembered “crying

on the field, right then and there. We’d achieved something I always wanted to achieve. I wanted to be a champion. That’s

why I ran into people with my face, to be a champion.” The Raiders were

angry afterwards, claiming that ruling of no-fumble on Lytle’s run cost them the game. After the game on national television, Dick Schaap interviewed Lytle. At the time, nobody realized

that Lytle likely had been out cold at the end of the play and wasn’t being coy when he said something noncommittal

when Schaap asked him about it. “So he [Schaap] said,

‘Let’s watch the replay,’” Lytle recalled. They watched it. “And then he said, ‘Now what

do you think?’ I said, ‘Well, you win some and you lose some.’” Lytle also recalled that the interview took place at the far end of the dressing room, just on

the other side of the wall from the visiting quarters. And there, he could hear Raiders coach John Madden yelling.

Among other things during the post-game discussions, Madden was telling reporters, yes, it was a fumble. In the next few minutes, Lytle told writers: ‘”At the time, I didn’t

think I had fumbled. Now that I’ve seen the replays, I feel very lucky. Somebody up there likes me. I was stopped, the

ball started to come loose, and it slid down my body. The referees couldn’t see it.” The Broncos countered that the zebras also had disallowed a touchdown catch by Denver

wide receiver Jack Dolbin, saying he had trapped the ball. In fact, he made the catch cleanly. Yes, two weeks later, the Cowboys easily handled the Broncos 27-10 in the Super Bowl in New Orleans. But that was anticlimactic. Sad to say, Rob Lytle died of a heart attack in November 2010 in his hometown of Fremont,

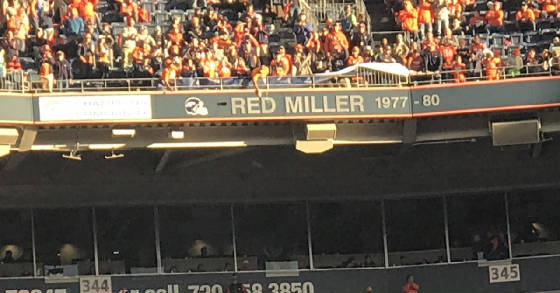

Ohio. Red Miller passed away

September 27, 2017, of complications from a stroke. At left, he is with his wife, Nan, at one of our periodic breakfasts at

New York Deli News shortly before he was stricken. Sadly, his November 19 induction into the Ring of Fame was posthumous.

Perhaps some

too young to remember that 1977 Broncos season, or those raised elsewhere, still are wondering what all the fuss is about

when the ’77 Broncos are discussed with such reverence around here. After all, they just made the Super Bowl; they didn’t

win it. Maybe you had to

be here. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|