Greg Ploetz is at left at joint reunion of ’69 Longhorns

and Razorbacks in 2004. Keynote speaker Terry Frei is second from right.

In 2004, I was

the neutral keynote speaker at the joint reunion of the 1969 Texas Longhorns and Arkansas Razorbacks in Fayetteville. The

two teams are forever linked by meeting in one of the landmark games in college football history — the Longhorns’

15-14 victory in a No. 1 vs. No. 2 matchup at Razorback Stadium.

I got to know many of the ex-players in the research process for my 2002 book, “Horns, Hogs and Nixon

Coming.” I was gratified that the ex-players said the book reminded them that they could be proud of being on the field

together on Dec. 6, 1969, in front of President Richard Nixon, future President George Bush, Sen. J. William Fulbright, Gov.

Winthrop Rockefeller and many other political figures — who sat together as a group in the stands. Rhodes Scholar Bill

Clinton, a Razorbacks fan whose Selective Service draft status was part of the book’s narrative, wrote in his autobiography

that he was listening to the game’s radio broadcast on a short-wave set in London.

There was a

lot more going on than football.

Arkansas’ black students and sympathizers were prepared to

storm and occupy the field if the school band played the song “Dixie,” and an anti-Vietnam War protest played

out on the hill above the stadium in full view of the president — but wasn’t shown on ABC.

One

of the ex-players at the reunion was Longhorns defensive tackle Greg Ploetz, an artist and art teacher in Fort Worth. I enjoyed

talking with him in 2001 and telling his story in the book, documenting that he was the son of a World War II pilot and spent

part of his youth in Colorado Springs, when his father was stationed there after remaining in the service. With the Longhorns,

Ploetz was a behemoth, at 5-foot-10 and 205 pounds. At UT, he was a fine arts major.

I signed a book

for his wife, Deb, who had gone to Arkansas.

Deb and Greg now are in the news.

Ploetz

vs. NCAA, the first Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy-related lawsuit against the NCAA, schools or leagues to go to trial,

is scheduled to open with jury selection Monday in Dallas.

Greg died in 2015. An examination of his brain

at the Concussion Legacy Foundation at Boston University determined he had Stage 4 CTE. That’s the worst there is.

Deb Ploetz, who later would sue the NCAA over

her husband’s death and CTE, gets an autograph from author Terry Frei at the 2004 joint reunion.

Deb, Greg’s wife of 37 years at his death, is the lawsuit’s individual plaintiff, along with

Greg’s estate.

The suit could have monumental national consequences.

In

advance of the trial, the NCAA subpoenaed and deposed me, and I turned over a tape of my book interview with Ploetz with a

clean conscience because the material about Greg in the book is a virtual transcript of what’s on the tape. There are

no surprises. And I’m not even sure which side in the suit the tape will aid more, if it comes into play at all.

What I do know is that Ploetz was a good man and should be remembered as more than a name in a lawsuit.

I’m going to try to personalize him here.

On the tape, Ploetz talks about how he initially

was listed as the freshman team’s fifth-team defensive end.

“I thought, ‘God,

I’m going to have to kill somebody,’” he told me. He said he took advantage of an “eye opener”

drill, where a tackler went one-on-one with a runner picking a hole between bags. He blasted the ball carrier. “They

picked him up, and I got up and somebody asked me, ‘Now what’s your name again?’” Ploetz recalled.

“The next day, my little ring is hung at starting linebacker.”

During the 1968 spring practices, infamous because

coach Darrell Royal made them a survival-of-the-fittest test after three consecutive 6-4 seasons, Ploetz had the “good”

fortune to get a reprieve because of an injury. He got caught in a pile and got up hobbling.

“I think I hurt my ankle,”

he told coach Pat Patterson. In fact, it was broken.

“All right,” Patterson said, “go in and dip it in something

and get back out there.”

Ploetz didn’t come back out to practice the rest of the afternoon. The next day, he pointed

to the cast and told Patterson, “I dipped it in plaster.”

As a sophomore for the varsity,

he played linebacker, then switched to defensive tackle in that monumental 1969 season. He eventually was named UT’s

top art student as a senior in 1971.

In the art department, Ploetz looked as out of place as a Haight-Ashbury refugee on

the Jester Center dormitory’s football floors. “I was pretty sympathetic with the antiwar movement, but I was

required to wear my fair short and I never participated in any rallies or walks,” he said. I had lots of friends who

did in the art department. It was kind of a joke over there. I only weighed about 205, but I was pretty bulked up. With short

hair, I’d go into a painting class and people would look at me and say, ‘Who’s that?'”

After practice

sometimes, Ploetz would head over to the art department to paint, which was his homework and release. It was as crowded as

football practice. “Your class was just a staging zone for painting,” Ploetz said. “Typically, I’d

leave [the canvas] on the floor to dry and then in the morning, when I got up, I’d run over there and roll them up and

put them in the rack. One time I forgot a painting on the floor. Mr. Spruce, a teacher I had, came in and said, ‘What

the hell’s this?’ He started to grab it and the kids said, ‘Do you know whose that is? The big guy with

short hair!’ And he said, ‘Oh, really?’ And so he put it to the side very carefully.”

His teammates

followed his work.

“As I took the life drawing classes, we had nudes, of course,”

he told me. “The guys would literally be waiting at the dorm: ‘Here he comes! Let’s take a look!’

… They’d get my pad out and look at the girls I was drawing.”

Ploetz had a

good game against Arkansas, helping keep pressure on Razorbacks quarterback Bill Montgomery. He had mixed feelings about shaking

Nixon’s hand during the president’s post-game tours of the two locker rooms. (He spent far more time on the winning

Longhorns’ side.)

“I wasn’t that crazy about the president at the time, but I shook his hand and got

to meet Billy Graham, too,” Ploetz said. “I sensed that because the president was there and he had come down to

see us, this was a special deal. So I shook his hand.”

Ploetz didn’t play in 1970.

He married a girl from back home in Sherman, Texas, and she gave birth to a son, Chris. He was very premature and Ploetz called

on the priest connected to the football team, Father Fred Bomar, to come to the hospital to immediately baptize the baby.

Chris’ godfather at the ceremony was Freddie Steinmark, the Longhorns’ defensive back from Wheat Ridge whose cancer-riddled

leg had been amputated six days after the playing in the Arkansas game. Chris survived. Freddie died in 1971.

(Because I also attended Wheat Ridge and was one of Freddie’s successors as a Farmers’ baseball

captain, I was steeped in Steinmark’s courageous story when I was in high school, and that was part of the reason for

my original interest in the Texas-Arkansas game, which I first wrote about at the 25th anniversary for The Sporting News. Longhorns starting guard Bobby Mitchell also was from Wheat Ridge. The only other non-Texan

starter for the Longhorns was halfback Jim Bertelsen, from Wisconsin.)

Ploetz also earned a master’s

in fine arts and taught at several schools, including Arkansas-Little Rock, and was divorced before buying, fixing up and

selling houses. He and Deb were married in 1978. He missed teaching, though, and settled in on the faculty at Trimble Tech

High School in Fort Worth.

Greg began having cognitive problems shortly after the 2004 reunion

and was determined to have frontal brain lobe damage and mixed dementia. At one point Deb brought him back to Colorado so

marijuana-based products could be used in his treatment. I visited Deb and Greg at the memory care assisted living facility

where Greg was living in the Denver area.

Deb told me that when she drove by kids playing football,

she wanted to pull over, get out of the car and lecture parents.

“I wanted so bad to go

tell them, ‘Do not let your son play football,’” Deb said.

In advance of the CTE diagnosis,

she told me: “I’ve never been a litigious person. I’ve never believed in that. Greg chose to play football.

He loved football. He would tell you his best years were with his brothers in football. He wouldn’t take that back.”

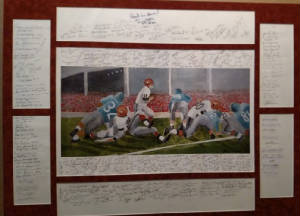

Greg Ploetz was deteriorating when he did this

football-oriented painting. Players from the Darrell Royal Longhorn era signed strips around the picture, and it was auctioned

off for Alzheimer’s research. Photo courtesy Billy Dale.

She changed her mind.

“After watching Greg’s last years of decline, I can say with all confidence, he would not choose to play

football if he knew he was going to suffer and die like he did,” Deb told me after the lawsuit was filed in 2017. “He

did not die from any other physical malady like a stroke, pneumonia, heart attack, he died from CTE. He literally lost his

mind and his life.”

The lawsuit charges the NCAA with a “failure to take effective action”

to protect Ploetz “from the long-term effects of concussions and sub-concussive blows to the head” he suffered

while he played for the Longhorns in 1968, 1969 and 1971.

It says the NCAA “failed to educate

its football-playing athletes, like Gregory Ploetz, on the long-term, life-altering risks and consequences of head trauma

in football.” It charges the NCAA “failed to address and/or correct the coaching of tackling or playing methodologies

that cause head injuries” and didn’t educate coaches, trainers and schools about concussion symptoms. And it argues

that the NCAA “failed to implement system-wide ‘return to play’ guidelines.”

Julius Whittier in his Dallas law office in

2001 during interview for Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming.

A former

Ploetz teammate and friend, attorney Julius Whittier, the Longhorns’ first African-American football letterman, in October

2014 was suffering from early onset Alzheimer’s. He also was a major figure in “Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming.”

He was on the freshman team in 1969, so he didn’t play in the landmark game, but was in the program. I interviewed him

in his Dallas office and also told his story. On his behalf, his sister, Mildred filed a $50-million class action lawsuit

against the NCAA on behalf of players who did not make the NFL but were suffering from brain injuries.

That

hasn’t gone to trial.

I have mixed feelings about this. It was 50 years ago. Retroactive judgment

or making blind assumptions that football and concussion issues led to the former players’ brain maladies — whether

dementia or, more specifically, Alzheimer’s — can be a slippery slope, at least before post-death CTE diagnosis

comes into play.

The football concussion “protocol” once was observation. Too often the

assessment was that you got your bell rung and, if possible, you went back in. The players thought that way, too. It’s

just the way it was. And not just in football. Apportioning blame now, both in this and the class-action settlement between

the NFL and former players, can lead to oversimplification.

There have been 111 similar cases —

the difference is that they’re class-action suits, and the Ploetz suit is against the NCAA only — filed over the

past two years. They’ve been combined into a multidistrict litigation (MDL) in Illinois federal court, and Zumado Public

Relations of San Francisco represents the former college players and attorneys involved in those cases. The firm notes four

of the cases were selected to be “sample” cases to be litigated “to help determine how this vary large litigation

should proceed.” I get that the motivation can be to provide funds for those needing help.

This

is just getting started.

—

UDATE: The two sides in Ploetz vs. NCAA reached an undisclosed settlement on June 15, the third day of testimony in

the trial.