The answer, as it turned

out, was two.

It seems so simple now. Go to Google. Search. Bingo. It wasn't like that then. You had to dig, explore, call, interview,

be patient. And then write. I'm fine with you being on my lawn, so that's not what this is. But there was something about

the quest, the connecting the dots, the archives, the clips, the lights going off in your head along the way rather than seeing

what shows up after you hit "Enter."

One of the baseball players killed in action was Harry O'Neill, who caught one game for the Philadelphia Athletics in

1939. He wasn't on the initial lists I found, but eventually I came across information about him (including, much later, in

the 2008 book, When Baseball Went to War). He was raised in Philadelphia and played football, basketball and baseball

at Gettysburg College. After graduating, he signed with the Athletics, but soon entered the Marines and was a first lieutenant

in the Pacific fighting. He was killed on Iwo Jima on March 6, 1945.

The other was outfielder Elmer Gedeon, who played five games with the Washington Senators, also in

1939. The Official Baseball Yearbook of '45 told me that Gedeon had 15 at-bats, three singles and a .200 average.

He was a big guy -- 6-foot-4 and 196 pounds -- from Cleveland. He died, the book said, in France, on April 15, 1944.

That

was his 27th birthday.

That's what I started with.

I set out to find out what I could about Gedeon. Was

he unique? In many ways, because he was a gifted all-around athlete, he was. In another very crucial way, as an American

who served in World War II, he wasn't.

So consider Elmer John Gedeon a symbol.

The story of his first

game was in the Oregonian's microfilm:

"WASHINGTON, Sept. 18 (AP) - Dutch Leonard won his

19th game of the season Monday when his Washington team defeated the Detroit Tigers 4 to 2."

Gedeon's name was spelled "Gedgeon" in the box score below. But he was there, playing

right field. One at-bat, no hits, one putout, no assists.

The lead picture in the sports

section that day was of tennis star Don Budge in London, carrying a book under his arm. The title: "Hitler's Mein

Kampf." The caption noted that Budge "is studying Hitler," whose German troops had invaded Poland on Sept.

1. Britain and France declared war on Sept. 3. World War II was two weeks old. Fifteen months before the U.S. entered

the war, Elmer Gedeon had played his first major-league game.

On Sept.

20, Gedeon's position was "m" -- or what the boxes then labeled center field. He went 3 for 4 in a 10-9

victory over Cleveland. Over the next three days, as Joe Louis was winning a title fight with an 11th-round knockout

of Bob Pastor and congressmen were pictured with stacks of "peace mail" on the back page of the sports section

("Lest we forget, let's stay out!") and Hitler was shown shaking hands in Danzig, Gedeon went hitless

his next three games.

He disappeared from the box scores for good.

The 1941

American League Red Book carried biographies of the Washington rookies, including one Elmer Gedeon, "recalled

from Charlotte. Gedeon, famous as a track man at the University of Michigan, is very fast and shows signs of being

a big-leaguer in another year."

But there was no evidence of Gedeon ever playing

another game, so I set out to find out more about him.

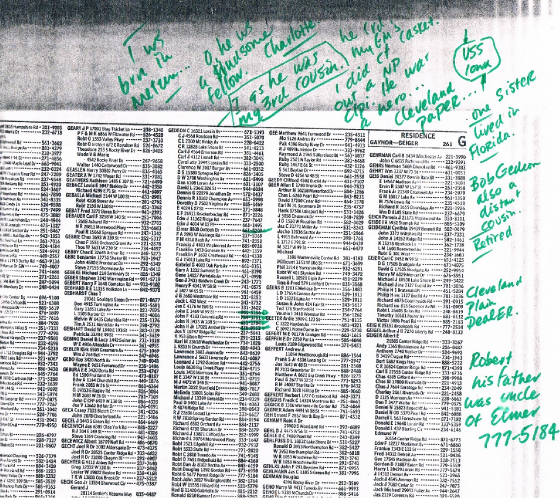

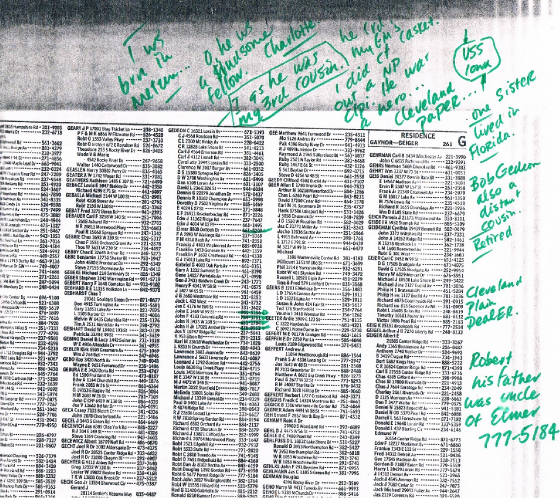

The Cleveland phone directory listed 97 Gedeons. There was one Elmer, on Outlook Drive. A

son, perhaps?

No,

said the woman who answered: Her late husband was named Elmer, but he wasn't the one who attended Michigan and played

for the Senators.

Thinking of his middle name, I tried the John Gedeons. Mrs. John F. Gedeon sympathized

and told me that the name was so common in her area because immigrants from Metzenzeifen, in the Sudetenland, were prone

to settle in Cleveland.

And Gedeon was a common last name in their native

land, she said.

The 10th listing, a "C Gedeon," turned out to be for Charlotte Gedeon. Yes,

she said, she was Elmer's third cousin.

"He carried my grandmother's casket," she said.

"Oh, he was a handsome fellow."

She told me to call Robert Gedeon, Elmer's first

cousin, and gave me the number for one of the nine Robert Gedeons in the phone book. Robert G. "Bob" Gedeon was

happy to talk about Elmer.

"We were only a year apart," Bob said, "so we were very close."

They used to play in Cleveland's Brookside Park. "One time we were ice skating and I

went through the ice, up to my neck," Bob said. "Elmer slid across the ice on his belly and pulled me

out."

He told of Elmer's athletic heroics at West High, then at Michigan in football, track

and baseball. Football, too? You bet, said Bob, a retired foundry worker.

Bob talked

about Elmer surviving a 1942 crash during training in North Carolina. Two of the six crewmen were killed.

Elmer won the Soldiers Medal, Bob said, for pulling a crewman out of the burning

plane. Rarrat's back and both legs were broken. Gedeon was the navigator on the training flight. Clippings from the Cleveland

Plain Dealer later confirmed that Gedeon suffered burns and required skin graft surgery, and also suffered three

broken ribs.

"The last time I saw him," Bob said, "he told me, 'I had my accident.

It's going to be good flying from now on.' He said he had used up his bad luck. That didn't turn out to be true."

Bob said Elmer's widow, Laura, moved to Florida. As far as he knew, Bob said, she no

longer was alive. Bob said that when Elmer was inducted into the Michigan Hall of Honor in 1983, Bob received Elmer's

plaque because he was the closest relative who could be located.

Next, a

look at the Michigan press guide confirmed that Elmer had lettered in football from 1936-38, playing with renowned

backs Tom Harmon and Forest Evashevski. The school's sports information department added some more details. (They came

from a young student intern who, I could tell, had no idea about Gedeon until he did the research for me, but he was

wide-eyed and impressed.) Gedeon also won two letters in baseball and track, hitting .320 for the baseball team

and holding American indoor records inthe 70- and 75-yard high hurdles. He was the conference's high- and low-hurdles

champion, both outdoors and indoors, in 1938 and '39.

Evashevski, the retired University

of Iowa coach and athletic director, was living in Petoskey, Mich., when I contacted him. "Oh, "Ged' was a

super guy," Evashevski said on the

phone. "He was a very, very humble person for a guy who had all his talent."

Evashevski

said they both belonged to the Phi Delta Gamma fraternity. "He recruited me," Evashevski said. "I asked

him what kind of guys they had. He said, "Well, all of them are about like me.' I joined. But the thing was, there

couldn't be too many like him."

Evashevski said Gedeon was a good, not great, football

end, but was remarkable in the spring sports. "He'd win the hurdles, then change uniforms and play for the baseball

team," Evashevski said.

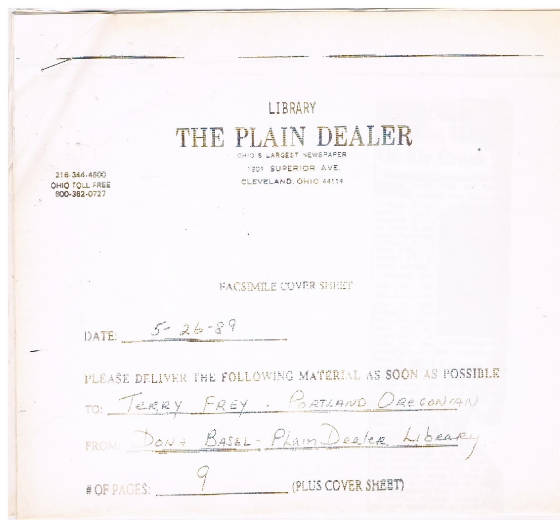

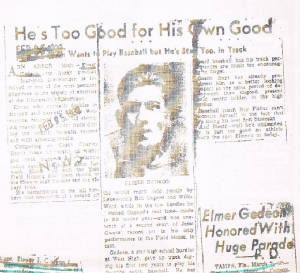

Dona Basel, a librarian at the Plain Dealer, FAXed me nine pages of copies

of its Gedeon clippings. One 1938 headline jumped out: "He's

Too Good For His Own Good."

1938

1942

In

June 1939, a week before commencement, Gedeon signed with the Senators, choosing baseball over a possible berth

on the 1940 Olympic track team. (The '40 Games, scheduled for Finland, later were canceled.) He joined the Senators when

they came to Cleveland in mid-June, prompting this headline in the Cleveland Press: "Campus

to Majors in 24 Hours - Saga of Gedeon." There was speculation that he would step in at first base for the

released veteran, Jimmy Wasdell.

Apparently unware that the Olympic track team would have

been determined in Trials, Gedeon told Howard Preston of the Cleveland News: "I'm not sure that I would have

been chosen for the Olympic team next summer but I heard I was being considered. Then I was chosen for the Big Ten all-star

(baseball) team which leaves tomorrow for a tour of the Pacific Coast

– and the itinerary includes Hollywood and the San Francisco Fair. If I signed a contract, I’d forfeit both trips.

So I thought it over and finally decided I’d better do something practical. Hollywood will be there a long time and,

well, there will be other fairs. So I signed a contract.”

(In later years, I came across someone who in some ways reminded

me of Gedeon -- 1936 Olympic decathlon champion Glenn Morris, a student body president, football and track star at Colorado

A&M/CSU from tiny Simla, Colorado who became the protagonist in my 2012 fact-based novel, Olympic Affair. Morris

won the Sullivan Award as America's top amateur athlete in 1936, in part because Jesse Owens had offended USA amateur sports

czars by turning pro virtually immediately after the Summer Games,. Morris starred as Tarzan in one movie, played briefly

in the NFL, served in the Pacific as a beachmaster in World War II and slid into oblivion.)

In another story in

the Cleveland Press, Gedeon said: “I don’t know what’s in store for me. If

I make the grade, I’ll probably be kept.”

Before he played game, the Senators sent him down to

Orlando of the Florida State League, where he was converted to the outfield. Returning to Washington, he got in those five

games at the end of the ‘39 season. He wasn’t ready for the majors, but it seemed a matter of time. He was with

Charlotte in the Piedmont League in 1940 and was recalled at the end of the year, but didn’t get in any Senators’

games. He went back to Michigan to coach the freshman football team in the fall of ‘40, was five hours short of a master’s

degree, and was preparing for another shot with the Senators when he was drafted in March ‘41.

He got in those five

games that season. He wasn't ready for the majors, but it seemed a matter of time. He spent the next season with Charlotte

in the minors, went back to Michigan to coach the freshman football team in the fall of 1940 and was preparing for another

shot with the Senators when he was drafted in March '41.

My friend Neal Rubin of

the Detroit News did a column on Gedeon in 2003,

citing my original research and quoting from my interview with Bob Gedeon, and then adding some new information. He located

an April ‘41 Phi Gamma Delta newsletter in which Gedeon told his fraternity brothers: “As you probably know by

this time, Old Ged has been drafted.” He thought it was funny that he had been assigned to the cavalry, adding, “the

only horse I ever saw in my life was the one the milkman used.”

He spent some time in the cavalry forces, then transferred to the Air Corps.

After his plane crashed during training in August 1942, when he was awarded the Soldiers Medal in Tampa, the Cleveland Press headline said:

"Gedeon Honored With Huge Parade."

An excerpt from the citation:

“After extricating himself, Lieut. Gedeon, regardless of the fact that he had suffered broken ribs and severe burns,

re-entered the burning wreckage and removed Corp. John R. Rarrat, fellow crew member, who had been rendered helpless in the

crash. Corp. Rarrat would have burned to death had it not been for the unselfish action of Lieut. Gedeon.”

By April 1944, he was based in England and was a B-26 Marauder pilot, the head of a crew of seven.

The Allied invasion of the European mainland was six weeks away. Gedeon wrote to his wife on April 19, then

left on a mission the next day. They headed to German construction works in Bois d'Esquerdes, France. The plane was hit by

German fire, burst into flames and went into a nosedive. Only co-pilot James Taafe made it out and parachuted to the ground.

Gedeon was buried at St. Pol. Later, his remains were brought to Arlington National Cemetery.

The Baseball Encyclopedia is five days off on his date of Gedeon's death. Below that, all you see is

that Elmer Gedeon appeared in five big-league games. He went 3-for-15 at the plate. That doesn't do him justice

-- both as a man and as a symbol.