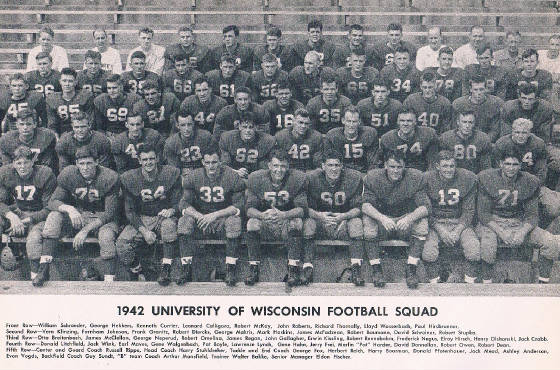

|

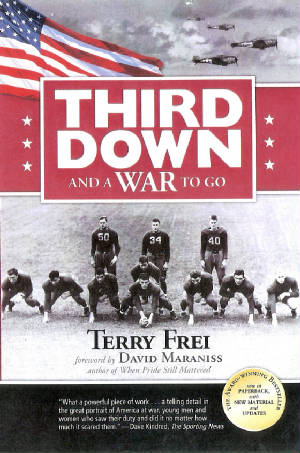

SETUP: The Badgers entered the final regular-season

game on 1942 with a 7-1-1 record. Coached by former Notre Dame "Four Horseman" quarterback Harry Stuhldreher, they

had beaten Ohio State in Madison 17-7 on Halloween the week before suffering a controversial 6-0 loss at Iowa when fullback

Pat Harder seemed to have scored in the final seconds of the first half, but the officials ruled that he hadn't crossed the

goal line.

The other blot -- if it could be called that -- on their record was a 7-7 early season tie with

Notre Dame. Sparked by All-American end Dave Schreiner, Harder and sophomore halfback Elroy "Crazylegs" Hirsch,

the Badgers were poised to finish out Badger football's best season in 30 years and perhaps even claim the Associated Press

national championship if voters considered the head-to-head game the tiebreaker for once-beaten Wisconsin and Ohio State. Going into the Minnesota game, UW was like most campuses around the country, with a

final-fling atmosphere prevailing as most men already had signed up for military service in the various branchers and were

awaiting callups -- which all knew would come soon. THIRTEEN

Bowing Out

The Badgers hadn’t beaten

the Minnesota Gophers in the schedule-ending rivalry game since 1932, so nine consecutive Wisconsin seasons had endedon a

sour note. The Gophers’ highly regarded coach, Bernie Bierman, left the Minneapolis campus after a second straight Big

Ten championship in 1941to serve in the Marines. His successor was George Hauser, who received considerable input from young

assistant coach Bud Wilkinson. By the final week of conference play for Minnesota and Wisconsin, the

Gophers had no chance to take the ’42 Big Ten title, but they could end any Badger hopes of succeeding them as champions—and

they could do it in front of a sellout crowd at Camp Randall.

On Sunday, manager Eugene Fischer’s

weekly note on the locker room chalkboard proclaimed: “Nine down and THE ONE to go.” The

Badgers had injury issues. During the week, quarterback Jack Wink and Paul Hirsbrunner, the other

tackle opposite Bob Baumann, shared a room in the university infirmary. Doctors determined Wink had suffered a strained knee

ligament in the previous game at Northwestern. Stuhldreher publicly proclaimed Wink would be involved in “at least partial

action.” That seemed farfetched,but among Harry’s plots that week was one to get Wink on the field—bum knee

and all.

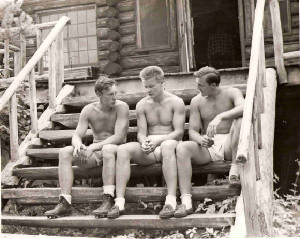

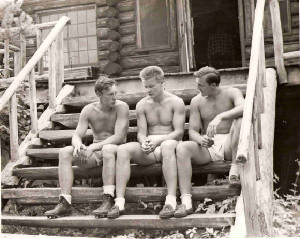

Camp Kooch-I-Ching counselors in the summer of '42: Wisconsin's Dave Schreiner, Minnesota's Bill Daley and Dick Wildung. Against Minnesota, Badgers All-American

end and co-captain Dave Schreiner would be facing his buddies Dick Wildung and Bill Daley, plus several other Gophers who,

along with Schreiner, served as Camp Kooch-I-Ching counselors at International Falls, Minnesota the previous summer. Again,

Schreiner spent some of his week scrambling to get tickets and telling his parents – in Lancaster, Wisconsin, in the

southwest corner of the state, one more time in a letter: “You were very foolish to let anyone in Lancaster know I had

tickets.” But he refused to take anything more than face value for the $2.75 tickets from anyone in Lancaster, although

he had to pay $6.50 for some of them because he felt he should pay his buddies at least what they could get on the open market. Stuhldreher again had a guest with him at the Uptown Coaches booster club meeting: Jay Berwanger, the onetime University

of Chicago halfback who in 1935 became the first Heisman Trophy winner. Berwanger was stationed in Madison as a Navy recruiter. The game had been sold out for over two weeks, and the athletic department announced that fifteen FBI agents were going

to be sent to Madison to foil ticket scalping. The FBI had far more important concerns, of course, so the much-trumpeted story

likely was both pure fiction and a preemptive strike, unless fifteen FBI agents had wanted to go to the game and had come

up with a reason to be inside the stadium while on duty. On game day, November 21, Stuhldreher

allowed Wisconsin State Journal newsroom columnist

Roy L. Matson to watch from the Wisconsin bench area and be in the locker room. Matson provided readers with an inside look

the next morning. On the first play from scrimmage, Wink’s replacement, Ashley

Anderson, boldly called for a pass. Elroy “Crazylegs” Hirsch hit Schreiner on the sideline, and Schreiner sprinted

the rest of the way for what seemed to be a 69-yard touchdown.

However, the linesman signaled that

Schreiner had stepped out of bounds at the Minnesota 41, triggering howls from the Badgers, who swore the All-American end

had stayed in the field of play as he ran past their bench area. (The game film confirmed that they were right.) The Badgers were unbowed. Pat Harder and Hirsch runs took them downfield, and Harder scored from 1 yard out. Only

two and a half minutes into the game, the Badgers were ahead 6–0. Matson told State Journal readers that Stuhldreher then turned to Wink. “All right, Wink!” he said. “Come on, Wink!” Amazingly, Wink—torn ligament and all—peeled

off his jacket, with the help of Fischer, and hobbled onto the field to hold for Harder’s conversion attempt. Wink put

his good knee on the ground and stuck the bad one out, straight. If a Gopher had wanted to play dirty, he could have “tripped”

over the extended leg. Nobody did. In fact, after the game, Stuhldreher told the scribes, “When we first thought of

using Wink to hold the ball for points after touchdowns, the players were worried about Minnesota players jumping on Wink’s

injured knee. I swear I saw several Gophers deliberately veer away from Wink when rushing in on the attempt to block Harder’s

kick. That thrilled me to think they would do that, when winning meant so much.” After

the touchdown, Stuhldreher’s strategy came into focus. Ashley Anderson left the game when the Gophers took over, and

Len Calligaro, normally a fullback, filled his defensive spot. Under the rules, substitutions could be made without calling

a timeout under some circumstances—including at the beginning of a half, after a touchdown or a conversion, or if the

ball had gone out of bounds. Otherwise, though, such changes required calling a timeout, and each team was limited to three

per half. Under this scenario, the Anderson-Calligaro shuffling meant the Badgers had to call “extra” timeouts

several times during the game, drawing 5-yard penalties for “too many timeouts” That meant the Gophers began many

possessions with a first-and-5, or the Badgers with a first-and-15. Anderson didn’t play a single down on defense. “I

think that’s the first time that kind of substitution ever was done,” Anderson recalled. “He did that the

whole game.” While Calligaro was on the field, Anderson donned a parka and stood at Stuhldreher’s

side, talking about plays the Badgers might use in the next series. Anderson kept one eye on the field, ready to scramble

to avoid players piling over the sideline, but he also had to keep twisting and turning to avoid the smoke from the cigarette

always between Stuhldreher’s fingers or in his mouth. When the coach raised his right hand to make a point or exhaled

after taking a puff, he nearly asphyxiated his quarterback.

Matson enjoyed the antics of Ken

“Roughie” Currier when the sophomore guard came out of the game for a short break near the end of the first quarter.

Currier worked as hard taunting the Gophers from the sideline as he did playing. “Hey, Frickey, you’re going to

fumble,” Currier yelled to halfback Herman Frickey. “Hey, Frickey, you better let it go.” To Minnesota quarterback

Bill Garnaas, Currier hollered: “Hey, Pee-Wee, you can’t pass. Look out, Pee-Wee, they’ll run over you.” Wisconsin’s second touchdown came on a 32-yard Hirsch pass to Schreiner, who broke Gopher Bob Solheim’s

tackle and dived across the goal line. The Badgers led 14–0 at halftime. Anderson

suffered a highly personal injury on the second-half kickoff, taking a helmet to the groin. As Anderson tried to gather himself

on the ground, Stuhldreher himself took charge, coming onto the field and giving his prone quarterback the traditional treatment

of repeatedly pulling him in the air by his belt and then lowering him to the ground. This time, the coach didn’t use

his usual line when players were injured: “Shake it off!” “Breathe!” barked Stuhldreher. Anderson was recovering from the original injury, but now he had a bruised tailbone. He stayed in the game and later

scored the third touchdown on a quarterback sneak, making it 20–0. Paul Hirsbrunner’s shoulder

hurt so severely that he had to leave the game. The “Indian” was in tears, both because of the pain and because

he knew he had just played his final down of college football.

A Bill Daley run got the Gophers

on the scoreboard late, but it only ruined a shutout. Stuhldreher managed to get his stars out of the game, hugging them individually

as they came to the sideline. He used twenty-five players that afternoon. As the final seconds counted down, the Badgers hugged

and cheered and popped one another’s pads. Final score: Wisconsin 20, Minnesota

6. Anderson had done a superb job of field generalship, primarily calling the plays and blocking and leaving the passing to

Hirsch and Harder, who each ran for 43 yards. Mark Hoskins, in his final game, blocked well and added 9 yards on seven carries.

Schreiner caught all three Wisconsin completions for a total of 82 yards. The athletic department had declared

November 21 Dad’s Day, and the players’ fathers were allowed in the locker room after the game. Matson recorded

the proceedings in the paper the next morning. Bert Schreiner, the Lancaster scion, called out as he crossed

the room.“Davey! Davey!” he exclaimed. “Oh, Davey, what a game!” Hirsch greeted his father, Otto. “Hi, Pop. How are you, Pop?” He reached over and pulled his pop’s

hat down, scrunching it on his head. Otto responded with a warm hug. “Aw, Pop,” Elroy said, embarrassed.

Then he noticed that a photographer wanted to take their picture. “Hey, Pop,” he said, “you better fix your

hat.” Seconds later, they faced the camera. Outside,

the Wisconsin band was playing its post-game show. The strains of “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” were

audible in the dressing room. The sting from the Iowa loss was diluted, though the Badgers realized it had cost them the Big

Ten title. They had gotten the word that Ohio State had beaten Michigan 21–7, and the day’s results gave the Buckeyes

the league championship by a half-game over the Badgers. “I’ve never been more

proud of a bunch of fellows in my whole life than I am this afternoon,” Stuhldreher told the scribes. In the press box, Roundy Coughlin wrote for his Sunday readers: “Boy, I’ll bet the Wisconsin boys in service

celebrated last night when that score went out Wisconsin 20, Minnesota 6. I’ll bet the closest tap room got an awful

work out. Did Schreiner ever play a game. Did you see him ride those blockers.That’s prettiest football picture I ever

saw. All the printer has to do is get the type set up for Dave Schreiner as the All-American right end.” He also had

kind words for Schreiner’s Lancaster buddy and co-captain, halfback Mark Hoskins. “The blocking and tackling by

Mark Hoskins was really a thing of beauty and he had that winning spirit in his body.” The Gophers’ Bill Daley said to the Madison writers, “It was a tough way to bow out, but I’m sure

glad it was Wisconsin and Dave Schreiner who finished it up for me. Isn’t that Dave a man, though? I’m sure proud

I became friends with him last summer. He’s a corker.”

Anderson’s fraternity brothers,

who had downed a few beers by the time the quarterback arrived back at the house, remembered Hirsch’s friendly teasing

in song after Anderson’s fumble in the Camp Grant opener. This time they serenaded Anderson as he came in the door: “Ashley, Ashley, we love

you, “Touchdown, touchdown from the 2.” Downtown,

the bars and taverns were doing ring-it-up business. A bellman told the State Journal

it was the busiest single night in Madison since the celebration following the repeal

of prohibition. “I think we sensed it at the time, that it was never going to

be the same, that it was the last hurrah of carefree college kids,” recalled Tom Butler, who celebrated the victory

that night as a UW freshman. “Our age of innocence was over.” The Badgers were about to be called to serve Uncle Sam. POSTSCRIPT: It cost the Badgers mightily when

the schedule was altered to add two military training camps with former college players in their lineups -- Camp Grant and

Great Lakes Naval Training Station -- and they ended up playing one fewer conference game than the Buckeyes. If both had

played the same number of games and had one conference loss, Wisconsin would have been the champion on the head-to-head

tiebreaker. And it seems likely the Associated Press voters -- a bunch of sportswriters -- would have honored that. Instead,

Ohio State -- despite the loss to the Badgers -- was voted No. 1 and the Badgers No. 3. The Helms Foundation, however, got

it right, naming Wisconsin its national champion. (Neither the Buckeyes nor the Badgers went to one of the four bowl games

-- Rose, Cotton, Sugar and Orange. Bowl games were considered add-ons and teams weren't penalized for not going to one. In

fact, the AP vote came after the regular season and before the bowl games, and that wouldn't change until the late 1960s.)

Schreiner was named an All-American for the second consecutive

season and won the Chicago Tribune Silver Football as the Big Ten's most valuable player.

Exactly one Badger returned to the varsity in 1943, and he

had a deferment to work on the family farm. The Badgers served in both theaters -- Pacific and European -- with great

distinction.

Two of their starters were killed

in action.

Seventy-five years later, the 2017 Badgers, with two members of the

heroic 1942 team honored on the upper-deck facade at Camp Randall Stadium, are attempting do what that team didnt quite manage

to do ... remain undefeated.

|