HOMEInstitutional Knowledge commentariesBioFilm rights, Screenplays, RepresentationOlympic Affair: Hitler's Siren and America's HeroTHE WITCH'S SEASONThird Down and a War to GoHORNS, HOGS, AND NIXON COMING'77: DENVER, THE BRONCOS, AND A COMING OF AGEMarch 1939: Before the MadnessPLAYING PIANO IN A BROTHELSave By RoyA Selection of Terry Frei's writing about World War II heroesThe OregonianThe Sporting NewsDenver PostESPN.comGreeley TribunePress CredentialsThey Call Me "Mr. De": The Story of Columbine's Heart, Resilience and RecoveryOlympic Affair: Chapter 1, Leni's VisitOlympic Affair: Chapter 15, Aren't You Thomas Wolfe?The Witch's Season Excerpt: Air Force Game, Bitter Protest, a Single ShotThird Down and a War to Go genesis: Grateful for the Guard, Jerry FreiHoneymooners Meet the Boys of SummerTommy Lasorda, the Spokane Indians, and My Summer of '70Smoke 'em inside: On Ball Four and Jim BoutonEarthquake at the World SeriesMosquito BowlA Year with Nick Saban before he was NICK SABANJon Hassler, Terry Kay and other favorite novelistsKids' sports books: The ClassicsBig Bill Ficke's Big HeartBob Bell's Food For Thought

|

| |

December 13, 2020

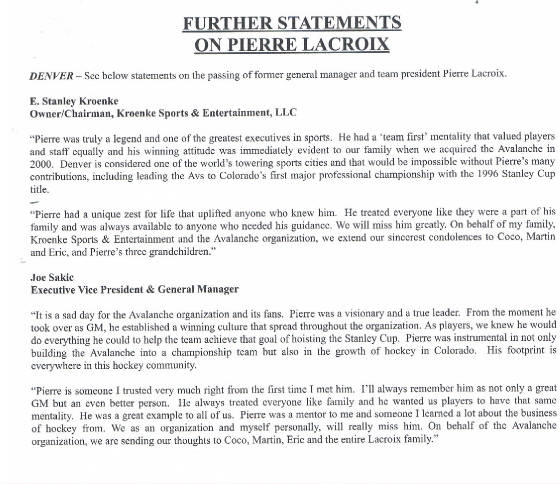

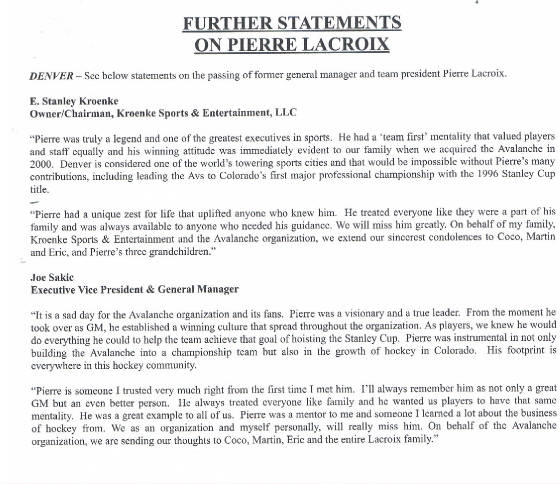

The Avalanche released the awful news:

Former team president and general manager PIerre Lacroix, who built Colorado's first major-league championship team and was

instrumental in making it one of the NHL's showcase franchises, died Sunday morning in Las Vegas. He was 72. The team didn't specify this, but Lacroix had been hospitalized with COVID-19. It seemed under control and he was

not on a ventilator, but he suffered a massive and fatal heart attack Sunday morning. Colleague Adrian Dater noted that Lacroix

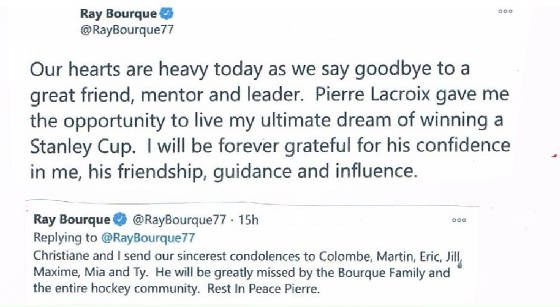

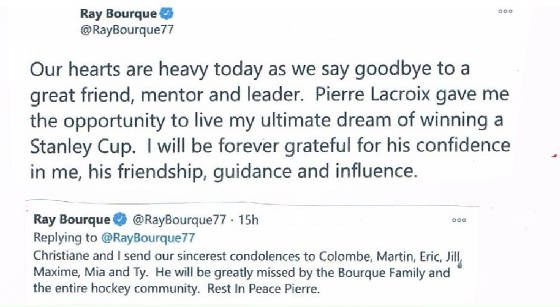

recently had visited his grandson, Max, in the Boston area, where Max is playing hockey and living with Ray Bourque.

The former player agent was at the Avalanche helm when Colorado won the Stanley Cup in 1996 -- the team's first season

in Denver -- and 2001. But there was much more to it, including the Avalanche's role in making the state one of the nation's

top youth hockey hotbeds, involving rink construction and hockey participation. Lacroix is survived by his wife Colombe, sons

Martin and Eric, and three grandchildren, and his death prompted me to look back at a few of the many stories and columns

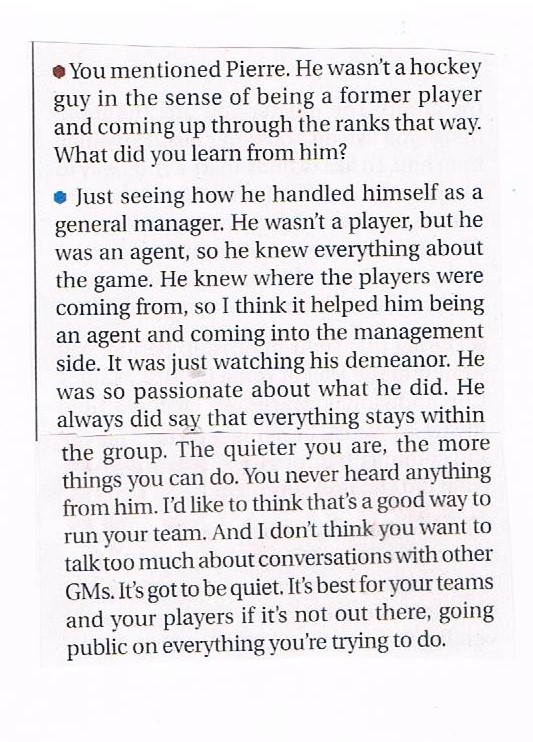

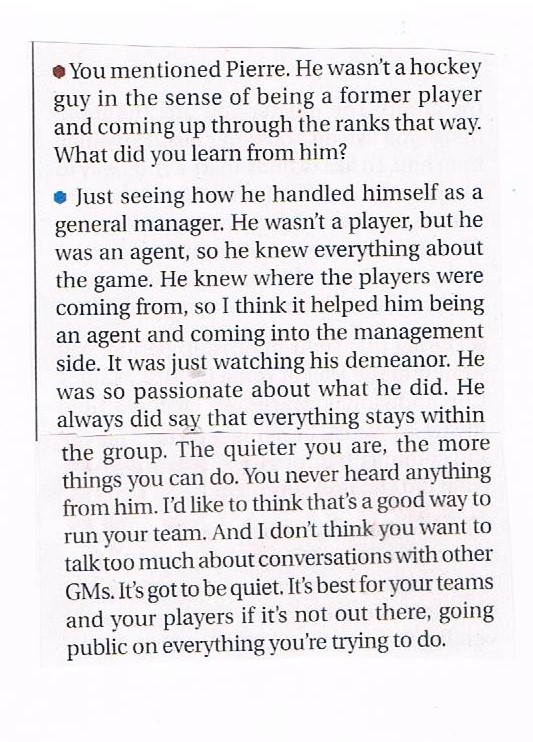

I wrote about him over the years. And to reflect. To start with, this is what Joe Sakic recently told me about Lacroix in my interview of of the former Avalanche star, who now serves as executive vice president and general manager, for the 200th issue of Mile High Sports Magazine:

So who was Pierre Lacroix? By the late 1980s, as a Montreal-based agent, he had a select client list

of about 25 players - including Mike Bossy, Vincent Damphousse, brothers Pierre and Sylvain Turgeon, and a young goalie named

Patrick Roy. He was not a slick attorney. He was a plugger. Pierre and Colombe's

two sons didn't have stars in their eyes -- they had them around the house. "I was the little brother to those guys," Eric said. "Even Patrick. He's 5 years older than

me. They were like family, and it helps you when you see your family succeed." Lacroix went from one side of the bargaining table to the other, taking over as general manager

of the Quebec Nordiques in 1994, then moving with the franchise to Denver in 1995. This much is indisputable: Lacroix played a key role in the Avalanche's stunning early success

in Denver, guiding the franchise through times both triumphant and difficult. The most challenging probably were early on

between the two Cup victories, primarily because of ownership instability and even chaos before the Pepsi Center empire ended

up in Stan Kroenke's control in July 2000. Lacroix was one of the constants

as the franchise reached the Western Conference finals six times in seven seasons from 1996 through 2002. Aided by the huge Eric Lindros trade made by his predecessor as the Quebec Nordiques' general manager, Pierre Page,

Lacroix built on that with shrewd stewardship during the Avalanche's early seasons in Denver. He added to a young core with

supplementary moves, including trade deadline acquisitions along the way. His legacy and semi-retired status was recognized

when he was inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame in 2008. The final major interview I did with him was in 2013,

when he officially shed the title of team president -- more on that later -- and stepped farther into retirement. "It's a legacy that everyone in the organization is entitled to," Lacroix said then. "It's

not a personal legacy. You're only as good as the people around you that help you do what you do in a team sport. . . I

feel like I've never worked for 40 years. It's been Friday every day for me. I was well surrounded, whether it was as an agent,

with clients or with people working with me as consultants because I didn't have the education and had all the legal advisers

and tax advisers with me. And the same way here. I can say that together, today we have created such an impact in this market

from the first day we came in. We won the Cup the first year, the state's first championship. There were three or four rinks,

a few years later there were 15. To have created that bond with the community was the greatest achievement." Charlie Lyons was the president of COMSAT Entertainment, the company that already owned the Nuggets,

then purchased the Nordiques and brought the NHL franchise to Denver. "Pierre was my dear friend and Godfather to my children," Lyons told me in

a Sunday email. "The Avalanche, all of Colorado and the sports world is devastated. Hockey lost a generational leader

and innovator. Most important, we lost the consummate family man. God Bless CoCo and the Lacroix family. Rest in peace brother.

Heaven is happy to have you." One of the things that tends to be underplayed or even forgotten

is that COMSAT mainly was shooting to land an NHL expansion franchise for whenever it could build a new arena in Denver. The

offer for the Nordiques was a shot in the dark, and a way to curry favor with the NHL if it could be used as leverage to secure

a new arena in Quebec City. Under those conditions, the move to Denver was sudden, and the

team played in the undersized McNichols Sports Arena for its first four seasons. The idea

that Lacroix was operating with an unlimited budget never was accurate, and especially so in the first few seasons. By the

Avalanche's second season, the ownership had evolved into the publicly traded Ascent Entertainment, and Lyons was president

and CEO -- and Lacroix's boss. "I was crazy about Pierre from the start," Lyons told

me for that 2013 story from Santa Monica, where he is CEO and managing partner of Holding Pictures. He added, "I

thought he was an incomparable blend of intellect, heart and in some ways most important to me, humor. Professional sports

is a tough place and there are a lot of different styles. His was almost like a Jerry Buss style, where it was, 'Look, you

have a choice, and you might as well create a family within an organization.' By doing that, you're probably going to have

more fun. "But, saying that, Pierre's a champion. Notwithstanding the relationships that

existed within that family, he was not afraid to make tough decisions. He managed to balance it masterfully with the fact

that he was loyal to a fault." Lyons said he never really had to say no to Lacroix, mainly

because Lacroix knew what to ask for -- and what was reasonable. "He would try to craft something," Lyons said.

"Whatever the resources were at the time, Pierre would give you the best possibility." Lacroix's

moves were many, of course, but none more significant than landing Roy in a December 1995 trade with Montreal. "I remember

the day he called me up," Lyons said. "He said, 'Patrick had a tough night in Montreal and he may be open and the

organization might be open to a move, and Charlie, all I can tell you is that if we get him, we will win, period.' I said,

'Do I need to know more than that?' He said, 'Nope. He costs what he costs and I promise you, we're going to win.' " With Lacroix in control of the Avs, the teams went through what amounted to de facto control of two

different ownerships -- those of Bill Laurie and then Donald Sturm -- before those sales were scuttled. Eventually, Ascent

took the teams back and they finally ended up in Stan Kroenke's portfolio. Lacroix kept his mouth shut and plugged along.

He probably never received sufficient credit for getting the franchise through testing times. Mistakes? Even Lacroix admitted there were some. "When I was in second or third grade," he said, "I

had this teacher who was nice to us and said, 'Hey, if you make mistakes, it's OK. If you do seven good things on 10 potential

things, you're going to end up in the next grade.' You make all kinds of decisions, and the important thing is that you try

and make them as you're trying to do them right for the team and for the fans." In addressing the Avalanche's slide after the early glory years, Lacroix conceded the league's

2004-05 lockout and dark season, then the implementation of a strict salary cap for the 2005-06 season, his last as GM, severely

affected the franchise. "The core was over $30 million," he said. "The lockout not only hurt us with the immediate

roster, but we had to go from $60-some million payroll to $39 million." He pointed out, though, that the Avalanche, a

bit uncannily, compiled exactly 95 points in four of the five seasons coming out of the lockout, and that was good enough

to make the playoffs three times. He said the NHL sought more parity with the salary cap ... and got it. He resented the misconceptions that he had won on an unlimited budget

and mismanaged the transition to the cap, and he even invited a handful of us in the Denver media to what amounted to a symposium

in the Avalanche offices. There, with a yellow legal pad on the table in front of him, he sought to explain his thinking in

the post-lockout transition. Beyond

that, he said the toughest move he had to make was trading Adam Deadmarsh, whose wife had just given birth to twins after

a difficult pregnancy, to the Los Angeles Kings as part of the package for Rob Blake in 2001, shortly before the Avalanche

won the Stanley Cup a second time. “I had to sit down with (Deadmarsh), whose wife and two kids were in the hospital,

and tell him he’s leaving,” Lacroix said. “That’s not a moment I wish I could go through again.” That 2013 front-office shuffling, he maintained, didn't

significantly change his role with the franchise. He said he had been primarily a team adviser -- albeit one with an impressive

title -- after he dropped the title of general manager in May 2006 and announced his semi-retirement at a Pepsi Center news

conference. The new GM was his one-time protege, Francois Giguere, who was returning from the Dallas Stars front office. That summer, Lacroix had the first of his several major health scares. Pierre and Colombe long had a home near Lake Las Vegas. This part turned to be sadly ironic: The Lacroixs

were there when Pierre originally feared he was having a heart attack. He had discomfort in his stomach and back, and when

he couldn't sleep, he called his longtime friend and Nevada neighbor, Rene Angelil, manager and husband of singer Celine Dion. "He's had two heart attacks and I asked him, 'What are the symptoms?"' Lacroix told

me. "He said, 'Burning sensation in the stomach and back pain."' Angelil was alarmed and took his friend to a Las Vegas-area hospital. Lacroix stayed there several days and underwent

an angiogram and other tests that determined he didn't have a heart problem. At least not then. It turned out, he had a suspicious

mass on his spine and doctors would gradually rule out various serious diseases, including multiple sclerosis. After an MRI, Lacroix was still having such severe pain doctors agreed it was best for him to

return to Denver for more tests under the supervision of Avalanche team doctors and neurologist Stan Ginsburg. Lacroix spent

two weeks in the intensive care unit at Rose Medical Center. He joked that at one point, he had been given so many steroids

he would have flunked any professional sports league's drug tests. "I had all the symptoms of something bad in my spine,"

Lacroix said. "That's why I was in such pain. … They told me they gave the maximum amount of medication my body

would take, thinking they would shrink that mass. It didn't work." The mass was in a spot that made a biopsy dangerous. Cancer was considered a possibility until spine specialists

at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota concluded after two Lacroix visits and yet more tests that a biopsy wasn't necessary; the

mass wasn't cancerous. "They told me they would have to monitor it, and

that I might have another reaction like I had a few months ago, but that there was, in their opinion, no need to go in for

any kind of surgery," Lacroix said. "You can't call it a tumor. You don't know why it hits.

It hit me and created this malformation of the spine. People live with pain in the back, and there's nothing wrong with that." He soon had more health issues, though, including a rare case of glue poisoning from a knee

replacement, and underwent five surgeries in a 33-month period. Still, Lacroix continued to serve as team president until

Josh Kroenke, Stan Kroenke's son, stepped into that role in May 2013. But, Lacroix said, despite perceptions to the contrary,

he hadn't been involved in the day-to-day operations of the franchise for many years. "In

my head, the way I look at it is that I became a resource for the organization and have stayed available for all these years,"

Lacroix said. At the news conference announcing Sakic's promotion, Josh Kroenke

confirmed that Lacroix asked to relinquish the title of team president in 2011, when Josh began to be more involved with the

hockey operation in his family's sports empire. Kroenke said at that time he and his father asked Lacroix to continue at least

officially in the role of president until Josh was deemed ready. That time came in 2013, with Kroenke becoming president of

the Avalanche, in addition to the Nuggets. "Pierre's legacy is one of many things," Josh

Kroenke said then. "He was one of the top executives in sports for a number of years, based on what we had on the ice.

I had a great relationship with Pierre. I have a great relationship with Pierre. He's helped lay the foundation of what we're

going to try to do moving forward." Sakic said that when Lacroix was in Denver, or when the

two men traveled together to NHL board of governors meetings, Lacroix was an instructor. Kroenke officially took over as the

team's governor (its representative at the league meetings) in 2010, but Lacroix usually attended as vice governor. "He's shown me the ropes, shown me how to do things and shown me his vision," Sakic

said. "He was kind of grooming me to take this role." Lacroix's handpicked

successor as GM, Giguere, served from 2006-09 before he was fired. Greg Sherman, who took over the job in 2009, ended up below

Sakic on the organizational flow chart and eventually left. Pierre's shadow

had been daunting. One of the many mysteries involving the Avs, sticking

to their drawn-curtain traditions established by Lacroix, was how directly Lacroix was involved in the decision-making process

and everyday operation of the team while serving solely as president from 2006-13. "I

just filled my role," he said. "I was a resource. When they needed me, they contacted me. The relationship has never

changed. The respect is mutual. I'm proud of another supporting thing I recommended, which was to bring Joe into the organization,

to get Joe involved, to have Joe learn the business. We need a hockey mind, a sincere guy that's got the respect and the integrity,

and Joe is the image of that. Joe's a sponge, he likes the world of business. He's sharp, he has a good hockey mind and he

wants to win. "This is how I could help. This is what I intend

to do if my health keeps going. It's always been the same. It's never changed since '06." Yet,

with Sakic becoming more than a high-profile face in the front office, assuming actual power, with Josh Kroenke adding the

title of president and with Roy taking over as vice president of hockey operations and head coach, Lacroix stepped even more

into the background. Lacroix said in 2013 that the franchise was in good hands

with Josh Kroenke. "I told Mr. (Stan) Kroenke years ago that Josh was young, bold and a had a good mind, let's get him

more involved," Lacroix said. "Now, the combination with Joe, it's going to be for the best. It's the right thing

for the team and for the fans. This is going in the right direction." And

his role? "Whenever they need me," Lacroix said, "I'm available."

He was. Up to the

end. I'll close with personsal remembrances. Pierre could become brusque when he thought he was treated unfairly

in the media. I was the brunt of his anger several times, and it could be the weirdest things -- as when I poked fun at one

of the first Burgundy-White games during training camp. I was amused by the rush to keep it short enough to pass NHLPA muster,

but neglected to mention that the game raised considerable money for youth hockey programs. As noted, Pierre was proud of

that and he was livid because he thought I at least indirectly had belittled it. Assessments of hockey moves?

At least with me, he didn't take that personally. And no matter what it was, he got over it. For

example, I didn't like the October 2002 Chris Drury trade to Calgary and probably should have let it go sooner than I did.

Even Drury told me later in Buffalo that it worked out for the best because he liked to play center, not wing -- and that

could be a problem on a team with pick-your-poison centers Sakic and Peter Forsberg. When Lacroix fired Bob Hartley 31 games

into the 2002-03 season, I was mystified. It was perhaps th only coaching firing I've ever covered that surprised me. But

that was because the Avs' meandering start that season had Pierre concerned about not winning a record eighth straight division

title, and that was a distinction he coveted. I also felt the Avalanche should have done more to demonstrate support for Steve

Moore. Pierre pointed out some behind-the-scenes things I didn't know about. It also was clear the NHL wouldn't have been

happy with the Avalanche doing too much for Moore while his lawsuit against Todd Bertuzzi and the Canucks was pending -- as

it was for nearly 10 years before it was settled out of court. In 1999, Pierre and Colombe lived

near Columbine High School. After the 13 murders on April 20, Lacroix not only went along with, he advocated the move of the

start of the playoff series from Denver to San Jose. The Avs still had home ice advantage and four games scheduled for Denver

after the shuffling, but playing the first two on the road certainy was a competitive risk. But Lacroix said it was the right

thing to do. Later in the playoffs, wounded Columbine students -- including Patrick Ireland, who as "Columbine's Boy in the Window" suffered nearly fatal injuries -- often were guests at games and in the

locker room. Then the next fall, Lacroix was influential in lining up Celine Dion to open the new Pepsi Center. Columbine

wounded and the family of the murder victims were among those sitting at the front as guests. Former Columbine principal Frank

DeAngelis raves about Lacroix. Dion met with them before the show, and she donated the proceeds to the Columbine mental health

foundation. (I am now wondering if widows Dion and Colombe Lacroix will become even closer. Angelil died of throat cancer

in 2016.)

In 2001, when my father, Jerry Frei, died, Lacroix and team vice president/PR executive Jean Martineau attended the memorial gathering. I thanked them. Pierre

told me, "At times like these, we're all family." My sympathies

are with Pierre's family.

|

|

| |

|

|

|